Columbus, Ohio USA

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com

The Art Gallery That Started It All

The Spangler Cummings Gallery

and the Rise of the Short North

By Jennifer Hambrick

May 2008 Issue

Return to Features Index

We all know about the Short North’s rags-to-riches climb from urban slum to art district. But how did it become the place where gallery after gallery proves that art is cool?

The Spangler Cummings Galleries, one of the Short North’s first commercial art galleries, had a lot to do with it. It was the gallery that started it all, and its proprietor, Melinda Johnson, had just the right resume and spirit of adventure to transform the Near North Side into the sparkling gallery district the Short North is today.The Birth of the Spangler Cummings Galleries

The Spangler Cummings Galleries was housed at 694-696 N. High St. for just over two years, then re-opened at 641 N. High, at the corner of Russell, as the Spangler Cummings Gallery in 1994, remaining for three years. Johnson, now 71, came to Columbus from Pittsburgh in 1983, when her husband got a job with Rockwell International. She was in her late 40s at the time and had almost finished a master’s degree in the drama department of Carnegie Mellon University. In Pittsburgh Johnson combined her training in dance, painting and sculpture doing production work for local theatrical performances. The playbill for one of the local productions she worked on during this time was the first document to bear her professional name, Spangler Cummings, a combination of her maiden name (Cummings) and that of her mother (Spangler).

In the late 1970s, Johnson also opened an art gallery and artists’ collective in Pittsburgh’s South Side neighborhood and watched the area quickly go from a blighted quarter to a thriving art district.

By the time Johnson arrived in Columbus, a group of entrepreneurs and concerned citizens were already looking for a way to develop the then-grotty Near North Side into a local attraction. Sandy Wood, who had left a career as a banker to start a business renovating older buildings, was front and center. He had seen the coast around the bay in Portland, Maine, redevelop as an art district and thought the same could happen with the Near North Side.“The neighborhood was trying to figure out what to do to lift itself up from its run-down condition,” Wood said. “A bunch of us talked about how we could develop the area and what types of businesses we could invite in to make it grow. Every Friday night we’d meet at the Short North Tavern to talk about what was going on. Ultimately we started working on art. I had a meeting with (Short North Tavern proprietors) John Allen and Greg Carr, and we decided whatever we brought in, it should be quality. We were trying to make the buildings look pretty and to provide something that Columbus didn’t have at that point, which was an emphasis on the arts and quality.”

Wood helped the non-profit art gallery ArtReach transition from the Yukon Building to Lincoln Street in the mid-1980s and wanted to bring in another gallery. He had heard that Johnson helped establish an art district in Pittsburgh. A building he was renovating at the southeast corner of High and Lincoln had an ideal gallery space. Wood asked Johnson to consider opening a gallery in the Short North.

“He came to me and said, ‘I have this space, would you like to do this here?’ And I said, ‘No, no these are my golden years. I’m just passing through town,’” Johnson said.

Wood convinced Johnson to look at the space, then a single shop front at 694-696 N. High St. The space, referred to as the Carriage House, because it had been an area for horse-drawn carriages to park while traveling up and down High Street at the turn of the century, was perfect for displaying art with two large airy rooms connected by an arched doorway.

She fell in love.

“It was this totally gorgeous space that the artists in Columbus were just wishing for,” Johnson said. “I said to (Wood), ‘Did I say no?’”

The Spangler Cummings Galleries opened on August 3, 1985.

Columbus Gets Art

Though initially Johnson balked at the prospect of running another art gallery in another derelict urban area, she took the plunge.

“Sandy said he would help me in every way he could,” Johnson said. “I said to him, ‘There is just one flaw: I don’t have any idea what I’m doing.’”

But that concern was soon outweighed by one more aesthetically important: Johnson was an artist living in a town where art had a surprisingly low profile. In fact, her first memories of Columbus’ art scene was – that there wasn’t one.

“I drove to the center of town to the State House and turned right to go up to see Ohio State, because that’s usually where the art district would be, and thought, oh gee, too bad. It’s all boarded up. That was my first impression, that there was no art district where I would normally see one.”

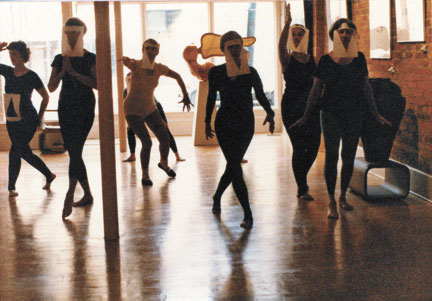

Johnson soon learned that Columbus had great artists, but that they had no visibility because there were so few galleries in town to represent them. In addition to ArtReach, Gallery 200 and the Keny and Johnson Gallery (now the Keny Galleries in German Village) were the only other galleries solely devoted to selling professional-calibre artwork operating in Columbus when the Spangler Cummings Galleries opened.Exhibition openings at the Spangler Cummings Galleries weren’t just see-and-be-seen noshes for Columbus’ would-be glitterati. They were all-out spectacles designed as much to rev up Columbus about art in general as to sell local artwork. At the Spangler Cummings Galleries’ first exhibition opening, pantomimes performed non-stop on the sidewalk in front of the gallery and escorted patrons in through the front door. Dancers also contributed non-verbal commentary on the artwork on exhibit. For a display of expressionistic art, dancers dressed in black leather costumes ran in to the gallery space and chained each other to poles. Dancers in diaphanous costumes once did modern dance for an opening of impressionist artwork.

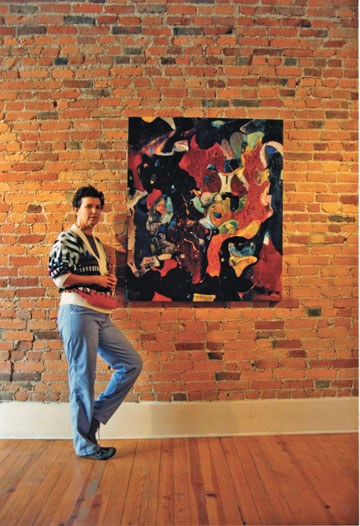

Melinda Johnson, aka Spangler Cummings. “This was theater,” Johnson said. “This was show biz. We knew they’d be talking about us around the water cooler on Monday morning. The whole thing was to create a show business atmosphere.”

It worked. Painter Michael McEwan, currently artist-in-residence at Capital University and an early Spangler Cummings Galleries artist, remembers Johnson’s gallery openings as novelties that drew huge crowds of art-starved Columbusites.

“These shows were huge,” McEwan said. “It was a lot of fun back then, the openings had gallons of champagne and tons of people. This was a new thing in Columbus. I had been part of similar things as a student in Washington, D.C., but not since my return (to Columbus) had I ever seen such a big crowd for an art exhibit outside of the museum.”

When the Spangler Cummings Galleries opened, McEwan and most of the other artists who showed there were near the beginning of their careers. Johnson wanted to sell art as much to launch the careers of local artists as to keep the gallery’s doors open. In choosing artists to represent, she didn’t pander to popular taste just to capture sales.

“It wasn’t the art that most people would want to buy,” Johnson said. “If you’re going to compare art to music, it was jazz, it was improvisation. It wasn’t popular music. It was the more cutting edge, improvisational art. We weren’t picking art and thinking, people will buy that.”

Artists whom Johnson represented remember that her first concern was for them and their careers.

“She really cared about the artists,” said paper artist Elena Osterwalder, one of the first artists to join Johnson’s roster. “She wanted to push us. Everybody wants to make money, but it wasn’t really so much for the money that she did it. She really has a passion for art and artists. That’s why she started (the gallery) and made it so successful.”

Johnson says she worked night and day beating the bushes for hot talent to represent, staging exhibitions, organizing openings and promoting her artists to collectors from Columbus and beyond.

“It was totally great fun,” Johnson said. “I didn’t even want to go to sleep at night, and then when I did, I woke up in the middle of the night and said, ‘Maybe if we tried it this way . . . .’”

Johnson’s tireless work launched a bevy of local artists into professional careers. Osterwalder had been having a difficult time getting her career off the ground, but Johnson’s gallery changed that.

“She opened the door for me. She absolutely launched my career as a professional artist,” Osterwalder said. “I had been exhibiting in a lot of juried exhibits in Columbus, but there were no sales or anything. And all of a sudden I’m in a gallery and selling, and with a record of selling that really launched my career as a commercial artist.”

When painter Sharon Dougherty came to the Spangler Cummings Galleries, she had completed a master’s degree in fine arts at Ohio State University and also had been making the rounds – with limited success – of juried exhibitions.

“She gave me my big break,” Dougherty said of Johnson. “Without her, who knows how long it would have taken? It meant the beginning of my career as a professional artist. I was able to show my work to people and they could count on going to her gallery and they knew she would represent my work. That was a springboard.”

Gallery District, Gallery Hop

Johnson and her gallery also were catalysts for developing the Short North into a gallery district. In the beginning, Johnson, local artists and the few other gallery owners in Columbus worked at least as hard at convincing other people to start up galleries as they did at establishing their own.

“To make this a success, you knew other art galleries had to be there,” Johnson said. “People who are interested in art galleries are also interested in food and antiques and other things that are made by artists. So everything that comes to the neighborhood is a great asset. It’s really important that it all be really plump with art. And all that came (to the Short North), some of the most fabulous galleries and places to eat.”

The Riley-Hawk Gallery opened up in the Short North at the encouragement of both Johnson and Wood. The Riley-Hawk Gallery opened not long after the Spangler Cummings Galleries opened and, with a roster brimming with the hottest young artists in the seductive medium of glass art, became a huge draw.

“The idea was that (gallery owners) would not so much compete, but cooperate, so people would have an area where they could go and see some art,” Dougherty said. “Rather than discouraging competition, I think (Johnson) encouraged it because it was better for the market.

I think it was a cooperative thing rather than a cut-throat thing.”

The result of this camaraderie was the emergence of a strip of modish art galleries in what had been one of Columbus’ most notorious slums.

“She got (the Short North) going as an art district for sure,” Sherrie Riley Hawk said. “It would have been harder to come here without Spangler having been here first. There was an exciting energy.”

As art galleries started popping up in the area, Johnson, Wood, Riley and other gallery owners began to develop a collective marketing machine to get the word out about the galleries in the Short North.

“(Johnson) started talking with the other gallery owners, (saying) ‘Let’s have our openings at the same time,’” Wood said. "First Saturday" gallery openings had started a year prior to Spangler Cummings Galleries move into the neighbrorhood, but Johnson gave the Gallery Hop its name and began working tirelessly to cultivate and promote it.The Gallery Hop was born.

Elena Osterwalder, one of the first artists to exhibit in the gallery, with her painting Zoology. Osterwalder remembers that it didn’t take long for the Gallery Hop to gain momentum and for Johnson to make art sales in an age when money flowed much more freely to the arts that it does today.

“Pretty soon it became extremely crowded,” Osterwalder said. “People got very excited about it. More and more people were coming, especially when the weather was nice. And a lot of people were buying art pieces right then and there. It was amazing how much sales she had during those Fridays and Saturdays. She sold over 150 of mine over the years that she was there. It was incredible. Nobody else has done that. They’ve sold a lot, but not as many as she did. I think it was a combination of, here we are, for the first time in Columbus, we are open Fridays and Saturdays and there’s something to do.

It was new to them.”

The openings and Gallery Hops were only the public aspect of the Spangler Cummings Galleries. Before the doors opened in the morning, all manner of artists would congregate in the gallery space for impromptu rehearsals and classes. Early morning yoga classes took place in the gallery, and a troupe of improvisational dancers came regularly to interpret the art on the walls through movement. Sometimes Johnson, herself a trained dancer, joined them.

“They were just enjoying the space,” Johnson said of the dancers. “It’s really hard to explain to non-creative types how somebody would just show up and start dancing. I know we looked crazy as all get-out to some, but to us it was fun.”Spangler Gallery II

All the creative mayhem came to a crashing halt when, on Oct. 20, 1987, the Spangler Cummings Galleries closed. Johnson’s husband was transferred to California. Johnson packed her bags for the West Coast.

“I cried and cried and cried,” Johnson said.

Johnson’s close colleague Roberta Kuhn took on her roster of artists and opened a gallery of her own on Russell Street. When Kuhn died in 1994, and with Johnson’s husband at that point retired, Johnson jumped at the chance to return to Columbus.

“I told my husband, ‘I wish I could go back and carry on for Roberta like she carried on for me,’” Johnson said. “And he said, ‘Why don’t you, and this time I’ll help you.’”

Johnson re-opened her art gallery as the Spangler Cummings Gallery in May 1994, and Johnson and her husband commuted between Columbus and their Malibu home for the next three years.

By the end of the gallery’s second run, Johnson was selling five times more art than she was when she first re-opened, but the business was still only breaking even. She says her second art gallery was never a “real business,” one that could sustain not just itself but also its proprietors.

“We started with no business, and we did sell hundreds of thousands of dollars of art by some artists who had never sold anything. It’s not like we didn’t help in some small way, but it just wasn’t enough,” Johnson said.

She closed up shop again in June 1997 and returned to California.

Developer Sandy Wood with his wife Barbara (right) and Cheryl Hayden at an ArtReach opening in October 1984. The idea that Johnson’s gallery was just the starting point for a whole neighborhood devoted to art, cuisine and interesting boutiques was visionary and has proved enduring. More than a decade has passed since Johnson left the Short North, but one can still see the fruits of her labors here on any drive up and down the Short North’s High Sreet strip. Today she recalls her experience as gallery director with a mix of renewed excitement and tender nostalgia.

“It was just so much fun. It’s just a great way to live,” Johnson said. “Every day you’re in the middle of this excitement and the art is just totally fascinating. You’re looking at their art. It’s just totally exciting.”

But it was also very difficult work, and Johnson is the first to acknowledge Sandy Wood’s role in making her gallery and the whole Short North gallery district possible. She says Wood offered her the space for her first gallery at a competitive subsidized rate, which enabled her to develop the gallery without fear of financial ruin.

“It’s very hard to make a go of a gallery,” Wood said. “I used to think restaurants were the hardest businesses to manage, but galleries are harder.”

Wood says he has subsidized other galleries, even to the present day. Why does he do it? Because he believes, as he and Johnson did in the 1980s, that Columbus should have an art district that makes life better for everyone.

“One thing I think the Short North had done is make art accessible to a broader area of the public. It seems that in a little way that’s what is important in life, that we try to make it beautiful for each other.”Updated June 2008.

© 2009 Short North Gazette, Columbus, Ohio. All rights reserved.

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com