Columbus, Ohio USA

Return to homepage www.shortnorth.com

The Great American Melting Pot:

A Walk Through the Past in Italian Village

December 2005

By Jennifer Hambrick

jmhambrick@yahoo.com

La Famiglia Piscitelli: Mama Maria Valentino Piscitelli with (from left)

Giuseppe (Joe), 3-year-old Automobile Aficionado;

Lorenzo Carmen, 5; Maria Antonia, 7.In 1903, Alfonso Piscitelli left the rolling hills and olive groves of his native Italy for America. He settled in Columbus, in the area of brick streets and town houses east of North High Street we today call Italian Village. He went to church every Sunday at nearby St. John the Baptist National Italian Catholic Church. He and his wife, Maria Valentino, raised their children in a traditional Italian Catholic home. Alfonso worked hard and, during the years of the Great Depression he worked hard to find work.

On December 20, 1927, Dr. Ernest Cox left his residence in Flytown bound for the Piscitelli home at 665 Hamlet Street. Later that day, Alfonso’s second son, Giuseppe, was born. In filling out the birth certificate, Dr. Cox spelled the foreign name just as it sounded, replacing the “c” with an “h.”

Today, Giuseppe, or Joe as he has always been called, still spells his name with that errant “h.” And today, Joe Pishitelli, 77, stands as a living witness of what life was like for Columbus’ Italian immigrant community during some of America’s most trying times.CHURCH

The area known since 1973 as Italian Village probably got its name because of St. John the Baptist Italian Catholic Church, still at Hamlet and Lincoln Streets. St. John’s was both a prominent Italian landmark in the area and a center of the devout Italian Catholic community. The church drew worshippers from most of Columbus’ Italian immigrant enclaves, including the St. Clair Avenue neighborhood, Flytown, Grandview, and Marble Cliff areas.

But the neighborhood around the church itself was ethnically mixed. During the early decades of the twentieth century, Columbus’ Italian immigrant community was one slice of a larger community of immigrants from all over the world.

“It was like an international village, but they got the name because of the Italian church,” Pishitelli said. “But you had everybody – Greeks, Irish, Lebanese, German, Polish, Italians – and they were all very compatible.”

Since St. John the Baptist Church did not have a school, the student body of nearby Sacred Heart School, on First Avenue, reflected the neighborhood’s ethnic variety.

“Sacred Heart School was kind of a great mix of nationalities, but nobody lost their ethnic identity,” Pishitelli said.

But at St. John the Baptist Church, everyone was Italian. Founded in 1896 and built two years later, the church’s mission was to help Italian immigrants keep their faith alive by providing them opportunity to worship in their native language and with the practices familiar to them from their earlier lives in Italy. In keeping with ancient Italian Catholic tradition still alive today, parishioners, all dressed in their Sunday best, would walk to church in major processions on the feast day of St. John the Baptist and other feast days that were celebrated in their native Italian hometowns.

“They would march from St. Clair Avenue down Second Avenue, to Fourth Street, to Lincoln Street and then go on to the church,” Pishitelli recalled.

Men in suits, women with lace head coverings and children in saddle oxfords and patent leather shoes mounted the steps into the church’s main sanctuary for the morning Mass.

Weddings at St John’s also were community events often ending in a home-cooked Italian supper.

“We looked forward to Saturdays because typically it would be mostly weddings when people can get together,” Pishitelli said. “After Mass, the altar boys would dart outside the church’s side doors to beat the wedding couple to the church steps. Family members and friends would line up on the steps and throw little comfits (Italian candies and almond nuts) – and they would also throw pennies, nickels, dimes and sometimes quarters when the wedding party went by and the kids would scurry around the wedding party to pick up the coins. After the wedding, the best man might invite all of the altar boys to go to the wedding reception and most of the time that was at Presutti’s Villa restaurant, on West Fifth Avenue in Grandview. People just loved their Italian food. Salvatore and Rosa, affectionately called Mama and Papa Presutti, were very affable people.”WORK AND HOME

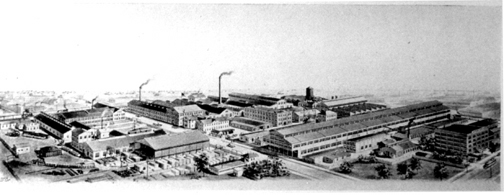

The Jeffrey Manufacturing Company, located between First and Second Avenues just off Fourth Street, employed as many as 3,400 workers, providing immigrant families with the measn to live.

Photo Columbus Circulating visuals collection at The Columbus Metropolitan LibraryEven before St. John the Baptist Church was erected at Hamlet and Lincoln Streets in 1898, the prospects of getting work within walking distance at the various manufacturers close by drew people to settle in the area. At the height of employment there were approximately 6,000 job opportunities in walking distance to the historic Italian Catholic Church. The Clark Grave Vault/Clark Auto Equipment Company, located at 375 East Fifth Avenue, had 1,200 employees. Traveling due south from their factories was The Jeffrey Manufacturing Company at 274 East First Avenue. A producer of coal mining equipment, Jeffrey’s had the distinction at one time of being the largest single employer in Columbus with 3,400 employees. East of the State Library of Ohio, there was the Berry Bolt Works at 30 East First Avenue that had 240 employees. Immediately south of Jeffrey’s factories, at Fourth and Warren Streets, was the Case Crane, Kilbourne & Jacobs Company with 200 employees.

“Then further south on Fourth Street near Goodale Street was the Smith Brothers Hardware Company employing 500 people.” Pishitelli said.

“The Radio Cab Company on Fourth Street and the Columbus Burlap Bag Company next door had a combined total of 200 employees. Then directly across the street from Radio Cab, you had Producer’s Oil where you could get gas for 16 cents a gallon. There were numerous other smaller businesses that easily brought the employment opportunities in this area to over 6,000 jobs, giving immigrant families of many nationalities the means to live.”

Immigrants to America in the early twentieth century faced an array of challenges. As they learned to conduct business in a foreign language and to adapt to the ways of their adopted country, industrialism forced them to acquire skills to cope with a modern world. People born in the era when the family horse was transportation died in the days of automobile travel. Those who grew up in Old World farming families sometimes found themselves making a living at manual labor jobs in American industrial cities.

Columbus, like everywhere else in the United States, was hard hit during the 1930s, and the immigrant community experienced its share of hardship during these years. But its people rose to the challenge of the Depression, exercising astute resourcefulness in looking after themselves and often performing acts of extraordinary kindness for each other.

“No one had money,” Pishitelli said. “But I was always able to make money because I would look for that opportunity.”

Alfonso Piscitelli did a lot of looking for opportunity during the 1930s. He lost his job in 1935 when the John Amicon Produce Company, Ohio’s largest produce wholesaler, downsized its workforce until forced into bankrupty. Alfonso’s redundancy placed the family in dire straights. Eventually he lost the deed to the family’s Hamlet Street home. Another Italian immigrant, Giuseppe (“Joe”) Priore, owned Priore Realty on the east side of High Street just south of Russell. He bought the Piscitelli house and several others that had belonged to families who could no longer afford to keep them at a sheriff’s auction. At the time, Piscitelli was unaware that his family had lost their home, since Priore allowed them to continue living in the house after he had purchased the deed.

Alfonso continued to look for work. And when he couldn’t find any, he made some up.

“People had to be very conceptual about having any income,” Pishitelli said. “The John Amicon Produce Company was located on East Naghten Street, right before you came to 4th Street. The trains would come with refrigerated cars to Naghten Street. These produce-refrigerated cars would have wooden slats holding chips of ice. With his push cart, my father would load up all these slats after the cars were emptied, and he would take them home and remove the nails from them. The wooden slats from these railroad cars were probably ten feet long and people would buy them for one penny each because they were very rigid and they could use them to make trellises and stuff like that. Even my father made short fences with them.”

Additionally, Alfonso worked with the Works Project Administration (WPA) and, as the economy picked up again, he secured a job at Mike DePalma’s Bar & Grill on High Street, where Rigsby’s Restaurant now is. He worked as a custodian at DePalma’s, cleaning up each day after it closed and setting up before the start of business the next morning, until his death in 1945 at age 61.

Joe Pishitelli himself took on jobs at an early age to help the family through the Depression. When he was six, he started selling newspapers at the corner of High and Goodale and later got a route delivering papers in the Short North area.

While he was playing near Smith Brothers Hardware, another Italian immigrant gave him a golden opportunity.

“The owner of the Radio Cab Company was Joe Palumbo,” Pishitelli said, “and he called me over to his big Chrysler convertible and said, ‘Hey kid, would you like to make some money?’ At this time my father was making fifteen dollars a week on the WPA and on a good night I could make a dollar and a quarter and find some spare change cleaning out the backseats of the cabs. I used to wipe off the cabs for a nickel each at the 4:00 p.m. change of shifts.”

When the worst of the Depression years were over and Alfonso Piscitelli found his steady job at Mike DePalma’s Bar & Grill, he once again became a homeowner. He bought back his house at 665 Hamlet Street from Joe Priore. Priore had bought the houses from families who could no longer afford to keep them so that they would not fall under government control. All along, Priore knew he would sell the houses back to their original owners, once they were back on their feet again.FOOD

“I’ve always said I’ve had the luxury of poverty,” Pishitelli said of growing up during the Depression. “We never had extra money, but we always had activities with other families, and we’d go to Goodale Park for concerts and to the Italian festivals on St. Clair Avenue. We never had new clothing, but they were always clean and mended. We never had a great variety of food, but it was substantial. Most importantly, we grew up with a strong religious family background, and we were also taught to be respectful of all people.”

Though paying for food was often difficult during the Depression, it was not difficult to find it at any number of stores nestled among the area’s residences.

“You would see a splash of small groceries in between houses,” Pishitelli said. “You might have six or seven in a neighborhood. In the area of Italian Village, the Wonder Bread Baking Company, at Lincoln and Fourth Streets, and Ward Bakery Company at Goodale and Hamlet. The first block north from there, at Poplar, there was a grocery store on the southwest corner. There was a grocery store somewhere on Fourth Street, close to Poplar. If you went east on Russell Street from Hamlet Street, there was a grocery store and a bar on the corner. West on Russell to Kerr was Salvatore’s Grocery.”

People rarely had cash during the Depression, so grocers would keep tabs and trust that their clients paid them when they could.

“The Italian stores would keep an account and my mom would give them so much money each week for the groceries and everything else she got,” Pishitelli said. “They made a lot of food, like pastas and chicken and they had a hanging prosciutto and they had olive oil. The environment was always oriented toward what they did in Italy and the foods weren’t expensive because they knew how to cook them and make them taste delicious. My dad grew vegetables and fruit in the back yard and mom canned them. My dad even had a fig tree that he had to bury every fall to keep it from freezing. The great mound of dirt to cover the fig tree looked like a dinosaur was buried there during the winter.”

If you could buy in bulk, Militello’s, a food wholesaler on East Naghten Street, had all the Italian foodstuffs you’d need.

“You could buy wholesale macaroni in great big long noodles,” Pishitelli said. “The noodles would make a curve that was connected together at both ends and the box might have 10 pounds in it. You could buy pecorino romano cheese, provolone, capacola, pepperoni, prosciutto, and olive oil. If dad came up with a little extra money, it was far better for him to go to Militello’s and buy wholesale.”THE NUMBER FOUR FIRE STATION

At the depths of the Depression, when people in Italian Village had neither money with which to purchase necessities like food, nor hope that they would find paying work, they could go to the Fire Station Number Four, at the southeast corner of Russell and Hamlet Streets. There, you could find provisions at the toughest times and, if you were a kid, you could just have fun.

“During the Depression, the fire station was the distribution center for people who were on relief, and that encompassed everybody,” Pishitelli said. “I’ll never forget one of the things was Oleo margarine. And it came in blocks looking like lard with a packet of orange coloring to mix in. There, you got potatoes, beans, flour, and it was always something that really made you feel good.”

And it wasn’t just the food that made people feel good. Pishitelli recalls that the firefighters always tried do something special for the neighborhood children. The Columbus Dispatch put out a call for people to bring broken toys to fire stations around town. The firefighters fixed the toys, painted them and gave them to children at Christmas. Even Santa Claus was there.

“Firefighter Potsy Miller, assigned to Station 4, was Santa Claus, but he didn’t need any padding,” Pishitelli said. “We really thought that he was the real Santa Claus because he knew all our names when we sat on his lap.”

Even during warmer weather, the fire fighters at Station 4 would bring the kids into the fold.

“They had a hydrant outside the fire station,” Pishitelli said, “and they’d hook up a hose and tell you to sit down on the granite pavers and then they’d aim the nozzle at your seat and the water would push you all the way across the street. They did many things to make the kids feel happy. They always tried to make kids feel important and that’s the best thing for a child to feel – important.”

Pishitelli says the firefighters at Station 4 inspired him to join the Columbus Division of Fire in 1953 and to remain with the division for 29 years.STREETCARS

Even if you were lucky enough to get work during the Depression years, there was still the question of how to get there. Streetcars offered an inexpensive alternative to foot travel about Columbus and opened up whole new worlds of experience for young explorers.

“My father never owned an automobile,” Pishitelli said, “but that wasn’t unusual, given the Depression, and you could get around on streetcars. My father would always use the streetcars. When you came to the end of the streetcar line and you had to go beyond that, you’d walk. They had many, many routes. They had streetcars going east, west, south and north. That was the biggest way of transportation. You could get a free transfer from one area to another.”

Pishitelli remembers that one of the routes ran straight through Italian Village.

“The streetcar would come down to where Summit Street ended and turn left onto Warren Street going for two blocks down to Fourth Street. It would turn right and then go down to Lincoln, then Russell, then Poplar Street, then Goodale Street and turn right and come back down to High Street and turn left (to go south) to get to the other side. That streetcar would also go all the way north to Oakland Park Avenue on Indianola.”

During the 1930s, 50 cents could get you to and from work for a week, and a kid could explore the world – or at least a small corner of it – for pennies. Pishitelli saw all different kinds of people on his journeys through town.

“A child would pay three cents for a passage on a streetcar. An adult six cent, but you could buy six of those tickets for a quarter. You could go to a lot of places for a very inexpensive amount. That was always a fascination to me as I grew up because I learned to be close to all of the different nationalities. And I learned what our country truly was: a melting pot of good hard-working people.”Photo Gus Brunsman III

Joe Pishitelli, lifelong member of St. John the Baptist Italian Catholic Church, stands with Father Metzger, St. John's current pastor. The church, located at Hamlet and Lincoln Streets, drew worshippers from most of Columbus' Italian immigrant enclaves in the early 20th century, including immigrants living in the neighborhood, an area that later came to be known as Italian Village.

CHANGES

Traces of Columbus’ Italian immigrants are all around the city, but much has changed since their first days in Ohio’s capital. Italian Village is no longer the immigrant neighborhood it once was. Italian still bubbles through the halls after Mass at St. John the Baptist Church, but the congregation’s American-born generations are replacing their native Italian predecessors. The streetcars that once criss-crossed Columbus are no longer with us (though with the help of dedicated citizens interested in restoring a part of Columbus history and reducing the city’s dependence on oil, perhaps they could be reinstalled). And instead of ethnic pocket groceries, the Short North area has beautiful, trendy pocket parks.

But possibly even more significantly, Columbus, though ethnically varied, is no longer a melting pot. And neither is America. The great emphasis on diversity over the last two decades or so, has, paradoxically, caused the idea of America as a melting pot to vanish from the national psyche. Diversity, which shares an etymological root with “divide,” emphasizes the ethnic and racial differences among people. The immigrants of the great nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American melting pot saw themselves as united by a common allegiance to their adopted land. Even though many of the old ethnic neighborhoods and shops of what we now call Italian Village are gone for good, the sense of community within diversity that made the area the true melting pot it was could, with a little effort, live again.

© 2005 Short North Gazette, Columbus, Ohio. All rights reserved.