Go to Home Page:

http://www.shortnorth.comMarch '02 Cover Story

Good Morning Vietnam: An American Photographer in the Land of The American War

By Kaizaad Kotwal

Harry Williams Jr. is a Columbus-based photographer who bought his first camera shortly out of high school. Williams's work focuses mainly on people, and some of his most stunning images emerged out of a month-long sojourn in Vietnam where he was able to capture the enigma, the soul and the history of a very complex and oft misunderstood culture and group of people.

Except for the aforementioned extended stay in Vietnam, Williams has lived in Ohio all his life. Born in Columbus in 1970, he lived on Warren Avenue until the age of 6 when his family moved to West Jefferson, Ohio. Eventually Williams returned to Columbus to attend college.

Born to Harry Sr. and Cruz Williams, the younger Harry has two sisters Helen, 32, Christina, 28, and one brother Michael, 17. The elder Williams, who has worked for Battelle for the past 25 years, was raised in Columbus on Neil Avenue. Cruz Williams, originally from El Paso, Texas, currently works in the cafe at West Jefferson High School. Williams himself attended West Jefferson High School and went on to do undergraduate work at Urbana College, Columbus State Community College and The Ohio State University where he eventually received his B.A. in photography in 1994.

Williams became a professional photographer right out of college; but upon graduating from high school, he had been uncertain what direction to go in. After purchasing a camera, he gradually acquired an interest in photography. "I bought a camera just to take snapshots of friends and so forth," he says. One of his friends suggested he take an introductory class in the medium at Columbus State. "I did," he says, "and I really enjoyed it."

After that initial love affair with photography, he transferred to Ohio State University. What cemented Williams's love for the medium was an internship during his college tenure at a commercial photography studio. "The owner of the business, Les Losego, and I became really good friends," he says. Losego became a huge influence on his art. "Even to this day," he adds, "whenever I have a question or need help with an art project, he is always there for me." Williams has displayed his work at The North Oak Gallery, The Wallich Gallery, Beyond the Canvas and various restaurants including Haiku, Lemongrass, and The Warehouse Café.

Williams's need to spend time outside of the darkroom, where he was doing most of his creative work, compelled him to explore other mediums. His explorations led him to a lot of experimentation with mixed media. "After I returned fr my first trip to Southeast Asia, I was really getting tired of all the time that I was spending in the darkroom," he says. "Also," he continues, "I was getting tired of looking at the same negatives over and over again, so I started mixing some of my images with objects, usually items consumed in large quantities, like beer cans and White Castle boxes." He also taught himself how to silkscreen.

Williams's many artistic influences include some of the world's most acclaimed photographers: Walker Evans, Minor White, and Robert Frank. Frank, a street photographer, had a book published called The Americans, and Williams remembers seeing these photos in the Wexner Center bookstore during his college days: "I was influenced by the way he photographed things that we see every day and just walk by, and yet he could make these mundane places so powerful." Williams is also enamored by the way in which Walker Evans photographed the depression era, capturing very ordinary people in very hard times.

Williams's work, too, seems meditatively focused on making the ordinary very extraordinary. I ask Williams what drew him to photography over media such as painting or sculpture. "I think it's because of how realistic a photo can be or cannot be," he says. "Sometimes when you take a photo, people get a totally different message than what you are trying to convey, and then there are times when people are right on the money. Or it's especially nice when someone sees something in a photo that you haven't thought about."

As for subject matter, Williams says that he loves to photograph people, mainly the minorities of different countries. Oftentimes, photographing minorities of different countries means capturing the world of people who live in conditions outside of the privilege of Western norms. Williams is not intent on exploiting images of "people who are poor and down and out." "But, it's funny," he continues, "how some people, when they see a photo will say, 'Those people are so poor.' I am really just trying to show the beauty of some of these cultures around the world that most people don't even know exist." And while it may be true that some of these indigenous populations live in material poverty, their spirits and cultures are rich in a plethora of different ways.

Williams spent nine months in Southeast Asia in 2000, traveling through Thailand, Malaysia, Borneo, Singapore and Indonesia. His second trip to the area, lasting eight weeks, was spent in Burma, Cambodia, and Vietnam; and, in his opinion, it was a lot easier. "I knew what to expect and how much to budget," he says. On his first trip, due to a family emergency, he had to leave and was unable to make it to Vietnam. Williams says that he really wanted to visit Vietnam to see for himself whether all the negativity associated with that country and its people was indeed true or not. "Most people think that it's a horrible place due to all the fighting that we did there," he says, "and most think that the people there hate Americans."

Williams started his Vietnamese odyssey in Saigon, "which was a crazy city and so packed with people on motorbikes and very few traffic lights, that crossing the street was insane." Williams however remembers the city as being "really amazing," and he loved the food, the people, and the old architecture, which is strongly influenced by the French colonizers.

The people in the south of Vietnam speak good English because of their alliance with the Americans during the war, with whom they continue to be friendly towards even today. American influences are to be found everywhere. "The thing that stands out in my mind," says Williams, "are all the markets that were selling fake Zippo cigarette lighters that were supposed to be from U.S. service men, that would have little sayings on them like 'I am never going to hell, because I have spent my time here in Vietnam.'"

In these Vietnamese street bazaars, Williams also found people selling dog tags and old U.S. army gear. He and his Hawaiian-born wife visited the War Crimes Museum, dedicated to what the Vietnamese refer to as "The American War." Someone in the Museum there told him that all this supposed war memorabilia was a sham, a complete fake. For him, it was a "real eye-opener," to see the war from the Vietnamese perspective. He was particu-larly taken in by some of the barbaric methods used to fight the Americans, the schematics of the underground tunnels, and remnants of American bombs, planes and uniforms. "These really blew me away," he says.

Williams and his wife spent their time in Vietnam mainly staying in the "back-packer's ghettos," spending around $5 to $15 for a room. The meals, which they often shared with the locals, cost a mere 25 cents on average. Williams found that eating with the locals had many advantages. "If I am sitting at a street stall, eating with the locals," Williams says, "it shows them that I am trying to live like them." This allowed Williams to gain their trust, which in turn made it easier for him to ask them to stop a moment and be captured by his lens.

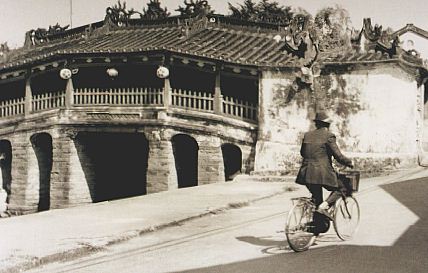

From Saigon he traveled by bus all the way to the north of Vietnam, stopping in a few cities along the way, his favorite being the city of Hoi An, which never experienced any fighting during the war. Williams describes it as an "old city with Chinese and Japanese influences, with a river running through the middle." It is on this river, in the heart of Hoi An, where people dine on the water under the light of handmade silk lanterns and candles.

"It's really one of the most beautiful cities I have been to in Southeast Asia," he says. Hanoi, on the other hand, according to Williams, was very different from all the other cities in Vietnam. "People there were very cosmopolitan," he says, and "it's a beautiful city but the people were not as friendly as in the South." They visited a museum in Hanoi dedicated to Ho Chi Minh, "which was really badly done," so they didn't stay long. From there his wife flew back home to Columbus and Williams traveled alone to Sapa where he hoped to photograph the indigenous hill tribe known as the Black Hmong, so called because of their clothing, which appears to be black because of the deep indigo dye used in the area.

Taking an overnight train to get to Sapa, which involved sleeping on hard wood with no blanket, he journeyed through the mountains bordering China. The actual city of Sapa was still a bus ride away from the train station. Williams describes this bus trip along mountain ridges, seeing different hill tribes working or just walking along the road as "amazing." Reaching Sapa, after that magical journey by bus and train, Williams checked into a place for $5 a night. Sapa was really cold and Williams was glad to have a fireplace in his room that he kept burning every night. "In the morning," Williams says, "before the sun would break up the thick fog, you couldn't see five feet in front of you."

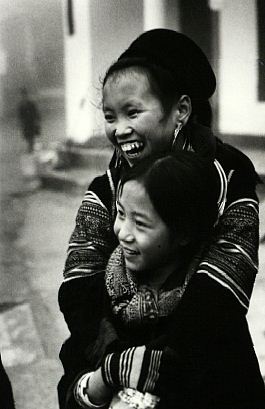

In Sapa, Williams regularly saw a group of young Black Hmong girls who would walk around and sell their handicrafts. "It was so funny to see all these girls, around the ages of eight to fourteen, trying to sell you bracelets and other trinkets," he says. Williams tried to speak a little Vietnamese to them, saying "Hello" and "What's your name?" The girls refused to speak in their indigenous tongue, choosing to answer Williams's queries in perfect English.

"I asked them why they didn't speak Vietnamese," Williams says, "and they said that they didn't like the Vietnamese." Williams made friends with this bevy of Vietnamese belles, joking around with them and getting to know the lot of them. The oldest girl Chai and her friends agreed to show Williams around the town. "Afterwards," Williams says, "I treated everyone to lunch at the market. We all ate a meal of tofu, pork fat and rice for a mere ten cents a piece and then enjoyed the rest of the day just walking around the town."

Williams spent a lot of time trying to blend in with the indigenous people and gaining their trust before asking to, as John Prine sang about photography, "steal a little bit of soul!" Williams says, "The one thing that I try to do when traveling is to learn as much of the language as possible and try to be as respectful as possible. I try and ask everyone who I photograph, for their permission, and it's amazing how well that works."

Williams also knows when to turn on the charm and when to use the universal language of humor to endear himself to his potential subjects. "In Vietnam I learned some of the local dialect from the Black Hmong hill tribe girls that I befriended," he says. "Just a few words or phrases like, 'I love you,' 'You're beautiful,' 'Will you marry me' or just 'How are you?'" Armed with these few phrases, Williams would walk into a village and say to the elderly grandmother that he wanted to marry her! "Everyone around us would start laughing," he adds, "because they wouldn't expect a westerner to speak in their dialect." "I would try to converse as much as possible," he continues, "then ask to take some pictures after spending as much time as it would take for them to get comfortable with me. Most of the people, I think, felt very proud to have their photo taken. Sometimes I would hand my camera to a person who was curious about it, and let them take pictures of me or their friends."

Having spent such a significant amount of time in Vietnam, I ask Williams what his views of that country and its people are. "My views of Vietnam are mixed," he says. "The country is really one of the most beautiful countries. Traveling along the coast you feel as if you're in Hawaii." Referring to the politics of the place, he says that he didn't really feel that the Vietnamese were Communists, but he was painfully aware of the different classes there, the rich, the middle class, and the poor.

Williams didn't like the way the minorities were treated. "On one occasion," he explains, "a couple from Britain and I were hiking up to a park above the town of Sapa, and all the hill tribe girls wanted to go with us, so there were around ten of us. When we got to the park gate we all paid the fee, but the girls were not allowed in the park. The Vietnamese official there said they had to pay the same amount as we did, which I think was a dollar, and he knew fully well that they could not afford such a rate." After arguing for a few minutes with the gate attendant Williams paid for all the girls to enter the park. The understandably offended girls "threw the money at the man."

Williams says that, "After that, my eyes were really opened to see how much the Vietnamese were exploiting minorities like the Black Hmong." He is struck by the sadness of the fact that the land that belongs to the people, where they once roamed free, is now open to them only for a fee, a rate many cannot even afford. But not all the Vietnamese were like the park attendant. Most, in Williams's estimation "were very kind and generous." On a number of occasions he was asked to join families for dinner or drinks by people he would just meet on the street. "And many times people would just want to talk to me to tell me how happy they were that Bill Clinton came and visited their country."

One of the most striking images from Williams's oeuvre, born out of his visit to Vietnam, is am extreme close-up of two hands belonging to an elderly woman. When traveling, Williams only shoots with a 50mm or a 28mm lens, so he has to get very close to his subjects. The image is simple in its composition, and the hands, front and center, marked with deep, deep lines have an abundance of stories held in those worked-to-the bones appendages. This image is reminiscent of Van Gogh's famous painting of a workman's boots, worn down to the sole, laces untied, leather battered and bruised beyond recognition, which in their stillness are flooded with the dynamism of its owner's entire life.

William's met this older Vietnamese woman several times as he was trekking. "Someone told me she was in her nineties," he says, "and that she could no longer work in the fields. But her hands were stained blue from so many years of dying clothes in the dye from indigo plants."

Williams worked for a day in the fields with the girls from the Black Hmong tribe, turning over the dirt so that the hill could be terraced off for rice planting. Williams admits that "After a half day of that, working with the family, my hands were covered with blisters and the girls were all laughing, saying that I must lead a very lazy life." The next day, he hiked back into the village where the elderly woman lived and photographed her hands, all the while imagining how many hard days in the field she had had in her long life.

Another stunning image is that of a young baby being carried on her mother's back. The baby on the mother's back was taken in Sapa town while Williams was walking with the Black Hmong girls. "The woman," he says, "who is carrying the baby was trying to sell me something, when I suddenly saw this head popping out of her back. I started to laugh, because I didn't see the baby at first. I told the woman how beautiful I thought her baby was and asked if I could take her picture. Like any proud parent she was really happy to have her baby photographed."

Williams's personal favorite photo from his trip is the picture of the hill tribe girl looking back at him. "I had already been in Sapa for week longer than most travelers stay," he says, "and I hadn't really taken any pictures of the hill tribe girls because they would ask tourists for money if they wanted a picture." These girls, four of whom were best friends, were his tour guides. "They took me to a park that was at the top of a mountain, overlooking the town. It was about an hour's hike to the top. When we finally got there we all sat and relaxed, taking in the view of the city. We all just kind of sat daydreaming when one of the girls started to sing a song in Hmong and it was such a beautiful moment," recalls Williams. It was during this perfect instant that one of the girls turned and looked back at Williams and he snapped the picture. "Every time I look at that picture it takes me back to that day."

Williams is full of stories and each tale is permanently etched out in a telling photograph. On another occasion, he was trekking alone and got lost when he encountered a group of Vietnamese men who were working on a dam that supplied power to the town. "They spoke a little English and invited me into their shack for some hot tea," he says. "They were also cooking lunch, in an old rusted pot over an open flame. The younger men asked me to stay and eat with them. The meal consisted of pork fat and rice and it tasted really good. After eating, the men got out the rice wine and we all started to drink shots." After around six drinks, Williams finally had to decline another, given that he still had to walk six miles back to the guesthouse. Before leaving he photographed everyone around the table toasting a shot and sent a copy of the picture to them when he returned to the States.

Having returned stateside, Williams hopes to start earning his entire livelihood as a photographer. For the time being, in order to pay the bills, he works as a consultant for Bath & Body Works with their visual team. "It has been great," he says, "because I am able to maintain a balance of working to pay the bills and working on my art." He also plans to return to Vietnam to photograph more of the hill tribe that he started to get to know during his last visit. He says that he would love to do a book on the Black Hmong, since there are no books on that or any other hill tribe of Vietnam. He hopes to focus on the day-to-day life of the family that he had gotten to know.

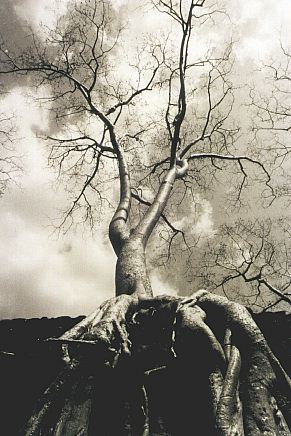

One of the reasons that Williams is so drawn to indigenous cultures is his concern that with the proliferation of Western values of mass consumption many of these cultures are endangered and on the brink of extinction. One of Williams's friends commented to him that his pictures are reminiscent of Edward Curtis's photos of the Native Americans. Curtis was known for capturing these tribes and cultures on the brink of extinction because of the encroachment of tourism and industry.

Once the cultures have vanished, all that remains are these images – powerful, yet mere snapshots of the real thing. Williams has visited and photographed other indigenous people including the Long-house Dayaks of Borneo. He says that in the future, he would love to photograph the remaining Hawaiians on the island of Nihau, another fragile culture with so much of beauty and value to offer.