Columbus, Ohio USA

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com

Doo Dah's Jack Decker

He's not just a Conehead

by Karen Edwards

September/October 2019 Issue

Return to Homepage • Return to Features Index

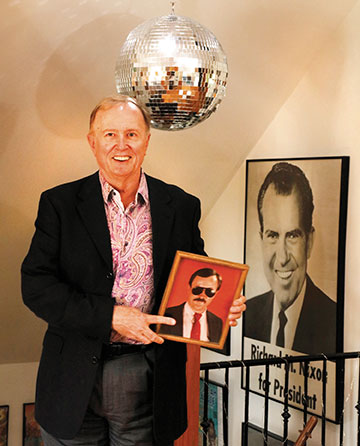

Jack Decker holds a photo of himself taken by Larry Hamill in 1987.

Photo © Larry HamillHe may be in a parade, but he does not march. Not in the Doo Dah or any other parade, thank you very much. “They’re too slow. I lose patience,” says Jack Decker, aka Conehead.

Yet for the past 36 years, Decker, dressed as his alter ego, has appeared at almost every Doo Dah parade since its inception. “I don’t march,” he says. “I just show up.”

There was a time when Decker did march. “I had a tuba which I played badly,” he says with a laugh. Given Decker’s personality, of course, you wouldn’t expect it to be just any ordinary marching band instrument. No, this one was a 1910 tuba with a cauliflower bell, welded together on a wing and a prayer. But it was the star attraction of the tuba-and-kazoo band Decker formed in the early 1980s, and which marched for a couple of years, at least, in the Doo Dah parade. “We played the Mickey Mouse Club song and ‘Over the Rainbow,’” Decker recalls. But the tuba got old and started to fall apart, so Decker retired the tuba and for the most part stopped marching.

But Conehead showed up at Doo Dah the following year.The Conehead origin

Now, there may be a generation of parade-goers who have no idea who or what a Conehead is – although Coneheads have been a part of pop culture since the late 1970s. For those unfamiliar with the alien family who showed up regularly on Saturday Night Live, the Coneheads (Dan Aykroyd, Jane Curtin, and Laraine Newman), who came to Earth as scouts studying humans ahead of a planned invasion, drank entire six packs of beer at once and consumed copious amounts of food, including inedible items like pencil shavings and fiberglass insulation. When asked about their strange behavior by their Earthlings neighbors, the Coneheads simply replied they were from France, and that seemed to satisfy everyone.

The Doo Dah parade does seem a perfect venue for a Conehead – identified, of course, by a smooth, cone-shaped head – but if you think Decker had been planning this act as a logical follow-up to his tuba/kazoo band, that he carefully and craftily built his costume, well, you can think again.

“I was at Yankee Trader one day, and saw this Conehead in a package. I had to have it,” says Decker, with the glee of an eight-year old who has managed to wheedle loose change from his mom for the gumball

machine.

But you have to understand a bit about the man beneath the Conehead to understand the reason behind the attraction and subsequent metamorphosis – for Decker is something of a character in his own right.

“I grew up in Marietta which is two hours from anywhere,” he says. Point in any direction to any larger city or town, “worth visiting,” he clarifies, and it will take you two hours to get there. His father was a self-taught refrigerator engineer “who held lots of patents,” and his mom a stay-at-home mother who dabbled in antiques. He has a brother, Jim, who now works “doing something in computers and artificial intelligence, and that’s about all I can tell you about that intelligently,” he says.

Decker briefly went to school in Philadelphia following his high school graduation, but came back to Marietta College to finish his undergraduate degree.Conehead comes to Columbus

Left to right: Michael Secrest, Barbara J. Austin, Joe Rutter, Maria Galloway, Cheryl Hayden, future "Emperor" Doug Ritchie (holding sign) and Jack Decker. This is from the first Doo-Dah parade in 1984. Photo © Ron Fauver “At about that time, the Vietnam War was in progress, and I was at an age where I was eligible for the draft, so I filed as a conscientious objector,” he says. “I was surprised when it was granted. After that, I came to Columbus to work at the State Hospital,” where, incidentally, his good friend from Marietta College, Rick Tully, was also working at the time.

It was the 1970s (just about the time the Coneheads were making their first appearance on SNL), and Decker managed to find a home in the South Campus area, around West Fifth Avenue – living in a beautiful, large home with three other guys. “It was great. I got used to living in splendor,” he says – and because his share of the rent amounted to $40 a month –“to having a large amount of discretionary income,” he adds.

Then, Battelle came onto the scene with dreams of a spreading campus. “They planned to tear down all the nearby properties,” says Decker, including that large, beautiful home he shared with his roommates. Fortunately, the plan to raze the neighborhood never materialized. Instead, the city started a gentrification program to improve the area and began looking for people to pour some money and sweat equity into the older homes that lined the streets of Victorian Village.

By then, Decker had finished law school and was in his first year of practice.

“A client came to me for a closing and told me the city was offering a three percent loan to those who bought one of their incredibly reasonable properties and wanted to improve the interior,” says Decker. “My client thought he needed an attorney for the closing. I told him he didn’t need much of one to handle this offer – and where could I sign up?” says Decker.

Decker thought, as an attorney, his income level would keep him from qualifying for the program, but the city rightfully concluded Decker was just beginning his practice and his income level would well- meet the program’s standards. In other words, Decker was invited to buy one of the low-cost homes. So, he paid the $7,500 and went to live in a house at the corner of West Third Street and Harrison Avenue. Of course, in the early 1980s, Victorian Village wasn’t the neighborhood it is today. “There was a Pentecostal Church nearby, and I could hear all their services.” And yes, there was crime and a certain amount of squalor. But it was home – at least until 1992, when he sold it, but he didn’t move far away. “I moved to a home on Neil Avenue about a block from the former abode that more closely approximates the splendor in which I had lived in the mid-1970s.” he says, adding a caveat, “It was at a far greater cost.”

Craig Copeland, a friend of Decker’s, and a member of the Doo Dah’s first Briefcase Brigade (he has long since retired his briefcase), remembers his first connections with Decker. “We used to play volleyball on Sundays in a vacant lot,” says Copeland. Tully, remembers the games as well, and the court. “It was nice – a real volleyball court,” he says.A Conehead-style ceremony

Then somewhere along the way, Decker married the now-late Barbara Austin. “Many referred to her as St. Barbara for having to put up with yours truly all those years,” says Decker. (Decker’s wife died August 26, 2017, after years of battling Type I diabetes, MS and heart disease.)

But back then, the Decker wedding was what his friends describe as typical Decker. It was certainly an occasion one might expect from a Doo Dah persona.

Jack Decker and his late wife, Barbara J. Austin, as “Twin Peaks” for the Doo Dah Parade. The tandem had a sign so proclaiming. “It was a major event,” says Tully. “And emblematic of who he is, as both Decker and his alter ego.”

What? Did he don his Conehead in addition to a tuxedo? No, not quite.

“Jack is a huge baseball fan,” says Copeland. “He is always studying baseball statistics.”

So, most of his friends weren’t surprised that Decker had rented out Cooper stadium, former home of the Clippers, for his wedding. And this was no typical march down the aisle.

“Jack and his bride ran the bases, then got married at home plate,” says Copeland. “It was the most unique wedding I’ve ever attended, it was well organized, but it was really beautiful too. It just worked.”

Decker’s marriage seemed to prompt an entertaining side, and he and his wife hosted plenty of friends through the years, at various dinners and parties. Copeland tells of especially lavish Christmas parties. “Everything was always done so well. Barbara had great style, even in the way she decorated the house.”

“Jack is a very social person,” says Tully. “If you don’t believe me, look at his Facebook page. He’s a prolific poster.”Not just a Conehead

Decker is also active in the community. “I was once very active in the Victorian Village Society, the forerunner to the Short North Civic Association,” he says. Then, when the Victorian Village Commission, which oversees the area’s rules and regulations, asked the society to recommend a member to serve on its board, the civic association named Decker. “I think they saw it as an opportunity to get rid of me,” says Decker with a chuckle. He continues to serve on the commission to this day and is an immediate past president of the Neighborhood Design Center. No wonder the Short North Alliance presented him with an “Unsung Hero” award last year.

Decker, by the way, is also a pretty good attorney, though, at this point in his life, he says he’s 90 percent retired.

“He’s brilliant,” says Tully. “He worked at the state attorney general’s office for years as one of their top appellate litigators.” Then, as an aside, Tully adds, “Jack’s also a history and Civil War buff with an almost encyclopedic knowledge of facts and dates.”

Civil war buff…baseball fanatic…commissioner...litigator…seems there is a lot going on under that cone-shaped head.

Although Decker and his wife never had children, Decker enjoys time with his rescued pit bull Samantha, “with some boxer in her as well,” he says – and the pair’s frequent walks are a familiar sight in the neighborhood. So is Decker on his bicycle. He’s an avid cyclist who can be spotted on many of the bike trails that wind their way through the city. “And I have a Victorian house which takes up the rest of my time,” says Decker.An iconic character

LtoR: is Emperor Doug Ritchey, the late Unofficial Parade Starter Joe Thiebert, 1986 Grand Marshall John Corby, the late "Mr. Doo-Dah" Bill Kiener, and an early edition of Beldar the Conehead. But he always carves out some time for the Doo Dah parade. “What else am I going to do on the Fourth?” he asks. As already noted, Decker has almost never missed a parade since its inception – though there was a period in the mid-’90s “when no one came,” says Decker. “Marchers would occasionally throw things out to the crowd along the route,” Decker explains. It was all in fun, but the crowd’s initial playful response soon got out of hand. “They were throwing things, largely water balloons, at the marchers, and were doing so from those third-floor balconies. It got pretty dangerous.” Sponsors started pulling out. So did participants. “The parade had lost its focus, but Doo Dah doesn’t die,” he adds triumphantly. Although the streets were quiet for a couple of years on the Fourth of July – no Doo Dah parade at all – it started up again, spontaneously. “People just showed up,” he says. And the legend of Doo Dah continues.

When Decker slips into his Conehead, he likewise slips into a character more fitting for the parade than his everyday persona – though friends attest that, even then, he is quirky and funny.

But as Conehead, Decker pulls out his inner goofball. He’ll ride his bike down the parade route before the parade, shouting to the assembled crowd that the parade has been cancelled. “No one believes me, though,” says Decker. When he is out circulating in the crowd he will give spontaneous weather reports, “And I ask passers-by for massive quantities of beer, though no one has ever given me any.” He wouldn’t know what to do with it if they did. “I gave up alcohol years ago,” says Decker. “I’ve already reached my lifetime limit.”

“People love him,” says Tully, referring to Conehead.

Sure, the original Coneheads of Saturday Night Live fame may have brought the Conehead image into pop culture, but Decker is the one who is carrying it on. He may well be the last of the Conehead race.

“Last year, I was at the parade,” says Tully, “and I usually go a little early, when the parade is beginning to form.” He knows a lot of the marchers and organizers and he goes to touch base, to lend his support. “I was surprised when a young couple, maybe in their mid-20s, went up to Jack and asked to take their picture with him.”

The couple were likely too young to be around for the original Conehead craze, or even the resurgance when the Conehead movie was released in 1993, but now, it doesn’t matter. For all intents and purposes, at least as far as the Doo Dah parade is concerned, Decker is Conehead. At least the only one this pair is likely to have known. “That’s what amazed me,” says Tully. “He has become such an iconic figure, that people know him, with or without the Saturday Night Live reference.”

That’s when you know you’ve arrived. That’s when you know you are Mr. Doo-Dah, master of minions, king of the carnival, grand pooh-bah of parades. You have become Conehead – the one and only.

But, please – just don’t ask him to march.

© 2019 Short North Gazette, Columbus, Ohio. All rights reserved.

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com