Personalities

|

Personalities

|

Remembering

EMERSON

BURKHART

By Tom Thomson

I was the last person to see Emerson Burkhart, the noted artist, before he had his fatal stroke - not counting, of course, Linda, the young blonde hooker he was with when I left his house.

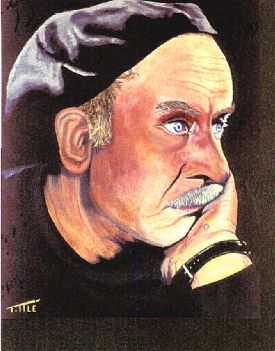

Portrait by Robert Tittle

Portrait by Robert Tittle

I had dropped by his big brick house on Woodland Avenue late one afternoon in November to see how he was doing. It was just a few days after his annual open house. I had gone to that and at the time I had thought he didn't look at all well.

Burkhart welcomed me with a big smile and invited me into the kitchen for a cup of coffee. Needless to say, the coffeepot was perkin' away on the stove so I sat down and made myself at home.

One of the first things he told me was that he had called this pretty girl - Linda - and that he wanted me to hang around so I could meet her. He seemed real proud. "She's smart as a whip," he boasted with assumed pride. "She's not only good in bed but I can talk to her about books and a lot of other things."

After I sat down at the kitchen table and began sipping the hot, black coffee he had poured, I studied his face. I had been right. He looked terrible, and I could tell that he knew it. Within minutes, he was complaining about not feeling good. "I looked like death warmed over on the TV coverage the other night," he lamented with a weak grin.

"Not that bad," I said, to buck him up, but I nodded my head sympathetically.

This was certainly not the cheerful, optimistic 64-year-old man I had known over the past dozen or so years. There was no one thing in particular that contributed to his appearance, it was just everything put together: his hands slightly shaking, sunken cheeks, sallow complexion - all of this in spite of the fact he'd just gotten back from a painting jaunt to a remote part of Canada.

By this time of his life, he had cut way back on his drinking - just a few beers now and then, but one bad habit he hadn't mastered: that was smoking, and it was pretty clear that it was killing him.If not a chain smoker, he was close to it, a cigarette dangled from his fingers almost constantly.

I could hardly tell him to quit smoking because I was a smoker myself. I had one burning in an tray on the table as we talked.

After I had heard him out, I tried to cheer him up. "You just need to take it easy for awhile," I suggested. "You've had a busy two or three weeks, getting ready for the show and all that."

"I know, I know, he agreed with me, and then his face lit up as he looked at his watch. "Now don't you go anywhere, Linda should be here any minute.

I grinned back at him and looked around the room. The walls of the kitchen were lined with paintings, mostly small to medium-sized ones, sometimes two or three deep.

I remember admiring a small painting of a bowl of eggs, five or six white eggs, beautifully shaded, and I made a mental note to ask Burkhart how much he wanted for it.

As it turned out, I never had the chance and all I can do is wonder where that little painting is today.

Burkhart was like a country doctor: he soaked the rich and took it easy on his friends and anybody else to whom he took a liking .

One of his pet peeves was the prospective buyer who wanted the colors to match some interior decorating scheme. This would fire him up so much that he would up the price of a painting to twice what he figured it would bring. Maybe three times.

I remember his telling how a Bexley lady came in with a swatch of cloth and wandered through the house looking for just the right matching colors.

She finally found what she liked in his upstairs bathroom.

"I told her that I was really in love with that painting. It's the first thing I look at in the morning and the last thing at night So I mentioned a price three times as much as I would charge anybody else, and I'll be damned if she didn't buy it!" He laughed at the memory and slapped his knee.

That last afternoon, I waited around until Linda showed up and let Emerson introduce her to me. She was maybe twenty, probably not even that old. Real pretty.

When I said good-bye, Burkhart had his arm around her waist and they were going upstairs.

He turned around and waved. "I'll see you, Thomson."

That was the last time I ever saw him.

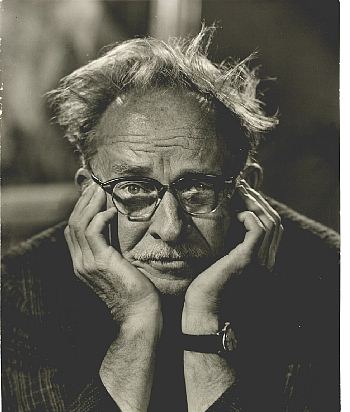

Emerson Bukhart, circa 1955

Emerson Bukhart, circa 1955

Part II.

I had left Emerson's house about five or five-thirty pm on a gray November afternoon in 1969. The last glimpse I had of him, he was going up the big front stairway, a smile on his face, his arm around Linda, the attractive young hooker he had asked over.

On the eleven o'clock news, I heard that he had suffered a severe stroke and was at Saint Anthony's Hospital.

Almost daily after that there were news reports as to how he was doing - in the press and on TV - but the news wasn't good. For eight days he was in intensive care, in a coma the entire time, his life hanging in the balance and, then he let go, and was gone.

His passing was noted by both daily papers, in editorials, and feature stories. A front page story with a picture of Burkhart, palette in hand, in the Columbus Dispatch, was headlined "Famed Artist Burkhart Dies," and went on to tell how from farm boy beginnings, he had gone on to fill thousands of canvasses with his reflections of life.

He was called a lively, articulate man, known as a wit and a philosopher; one who was never sure he believed in "destiny" and who credited his tremendous painting output to accidents.

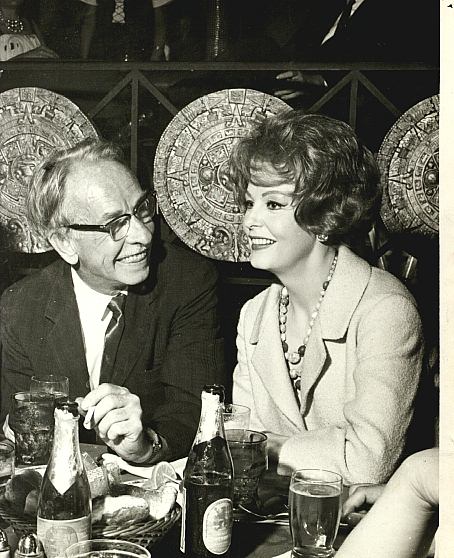

An exuberant

Emerson Burkhart chats with film star Arlene Dahl

over after-dinner drinks at the Kahiki Restaurant.

"You're born to a mother and father," he was quoted as saying from some past interview: "You didn't choose them. You're born at a certain time -you don't choose that either - and the rest is probably accidental too. Why am I a painter? Seven hundred accidents, I guess."

The article mentioned that he never knew for sure how many paintings he had done or, for that matter, how many he had sold.

But, he did know that one of his works was hung in the Metropolitan Museum in New York City, and that other paintings resided in quite a few other nationally known galleries and museums.

A front page story in the Citizen-Journal by staff writer Betty Garrett asserted that he was a man who milked every minute of his life, so much so that some of his friends took it for granted he was really stronger than time, and would go on indefinitely.

It is a strange comfort, she continued, that most of this wouldn't have mattered to Emerson Burkhart."

"Why are people always worried, about dying and immortality?" she remember his once asking, and he had answered himself.

"You can't get out of here alive. No way. And who wants to? They can flush me down the commode when I leave, it makes no difference to me. I'd get back to Big Walnut Creek that way, and that's life, and it's life that's everything."

Garrett quotes him as saying that he claimed no religion except life, the five senses, and participation.

Later, from what I read, and from talking to mutual friends, I was able to piece together some of the events that transpired that last evening at his house.

He had gotten sick while Linda was still there and she had panicked. Scared to death and probably feeling guilty as sin, she had dressed, hurried down the steps, dashed out the front door, inadvertently locking it behind her.

She hurried down the street to a telephone booth and from there she had called for help.

The emergency squad had to jimmy the door open, and when they rushed upstairs they found Burkhart unconscious, sprawled on his bed.

When I heard that he had died, I was very sad. because I had counted him as a dear friend. Over the past dozen years of his life, I had often dropped by his house just to say hello, chat a while, and gaze with admiration at the many paintings that hung on the walls in every room.

It was true that Burkhart was an avowed atheist, a non-believer from the old traditional conservative school of doubters - as American as apple pie, he used to say. His beliefs coincided with those of Robert Ingersoll the friend of 19th century presidents, Thomas Edison, Clarence Darrow, and the highly popular Mark Twain.

"Read The Mysterious Stranger, by Mark Twain, then come back and tell me that there's a God," he was apt to tell anyone who was foolish enough to get into a religious discussion with him.

I remember having lunch one time with Emerson and Milt Farber, a downtown attorney and, oh boy, did they get into it! They ended up yelling all kinds of insults at each other. Farber was so angry he pushed his chair back from the table, shot one last pious remark at the smiling Burkhart, then stalked out of the restaurant. He was so steamed up he forgot to pay his check. Or maybe he didn't forget.

Burkhart and I would meet once or twice a month at some downtown restaurant, have a drink or two, then have lunch. Or sometimes I would just run into him, on the street, or in a restaurant. Burkhart was a party animal. No doubt about that.

Those were the days when there were many fine places to eat and drink in downtown Columbus. We would go to places like Benny Klien's Steak House, the Hour Glass in the Deshler Hotel, the Town and Country Room in the Neil House, Marzetti's, the Maramor, the Key Club, the Top of the Center, the Bismark, and Kuehning's.

I will never forget one humorous episode as long as I live. Burkhart had called me at the office one noon and I had agreed to meet him about four o'clock at the Press Club. That's when it was down the alley on West Lynn Street, behind the old Journal building.

Emerson looked the part of an artist, what with a beret pulled down almost to his eyebrows, a loud sport coat, and paint-splattered pants.

When he showed up, I was talking to Gene Grove, the cop house reporter for the old Columbus Citizen.

Gene was telling me about a place over on N. Fourth Street called the Kismet. It was a gay bar, he said, but the owner welcomed straight people so long as they didn't cause trouble, or start proselytizing about the virtues of the straight life.

"A lot of really interesting people go there, both men and women," Gene said. "The owner's a real nice guy," he continued. "His name is Eddie Santousi. If you guys would like to check the place out, I'll call Eddie and tell him to treat you right."

Well, by gosh, that's what we did , and let me explain one thing right now. Gene was straight as an arrow, and so was I, and so was Emerson. The truth was nobody could have liked women more than any one of us. We just didn't harbor any mean feelings or prejudices against people who were a little different from us.

Emerson and I got in our cars and we buzzed over to the Kismet. He had a snappy little red convertible, a few years old, but still sharp. I think it was a BMW, or something like that. He usually rode around with the top down, just like you'd expect an artist to do.

It wasn't even five o'clock yet and there weren't many people there yet. Two or three fellows were talking at the big circular bar and a handful of guys and dolls were sitting at tables, or in the booths along the wall.

So there we were sitting at the bar having a beer when Burkhart's wandering eye spotted these two attractive women, one black, one white, holding hands in a booth.

Before you could say Mrs. Robinson, he had shot over to where they were sitting and in his most ingratiating way stood there talking up a storm.

Kicked his shoes off

I couldn't believe it when they asked him to sit down. Well, he flops down in the booth opposite these two gals and he's just gabbing away like there's no tomorrow.

I almost fell off my bar stool at what happened next.

The two girls had gotten up to put money in the jukebox. In the meantime, Burkhart had kicked his shoes off, gotten up and there he was out in the middle of the floor dancing with both girls at the same time.

His new friends were giggling and laughing as all three of them dipped and swirled around the little dance floor. As for Burkhart, he had a grin on his face a mile wide.

Well, you can see that for a good many years during the late 50s and early 60s, Burkhart made living in Columbus a lot more interesting and intellectually stimulating for me than it otherwise would have been.

Part III)

Gadfly to Columbus, Ohio, and the world, Emerson Burkhart - in the fashion of Socrates - was not only an artist, he was a philosopher and keen observer of human nature. His memory lingers on in the minds of those who were lucky enough to have known him. He was a remarkable man. Truly, an American Original.

Burkhart's house

on Woodland Avenue.

I remember one snowy afternoon sitting in the kitchen of his house at 223 Woodland Avenue with a couple of mutual friends. A pot of coffee was perkin' on the old cast-iron stove and we were having a great time - mostly listening to Emerson expounding on the condition of the human race.

His mind would move easily from one subject to another and on this occasion he got into a lengthy discourse on the subject of chairs.

Can you believe that? Talking about chairs? Making it so interesting we were hanging on his every word.

The subject came up in a round-about way that had started with art, style - and as usual, women.

"Styles come, styles go," he had started off. "Changes of dress, ways of wearing the hair. Women used to wear bustles - emphasized their rear ends.

Why did they want to emphasize their rear ends? Because men like that part of a woman's anatomy.

"Men have always loved firm, smooth, accentuated buttocks. They're one of the great pacifiers. " He grinned and sipped at his strong, black coffee.

"The buttocks constitute one of the greatest sculptures of all time," he continued. "And they are not just aesthetic, they are one of the most marvelous engineering accomplishments on the face of the earth.

"The buttocks make it possible for us to walk and, more importantly, to sit down.

If we didn't have 'em, what would we sit on? And even if we could, look how uncomfortable it would be sitting on nothing but bone and muscle." He chuckled at the mental picture he had drawn, sipped at his coffee, and lit another cigarette.

"As it is, we have a nicely shaped layer of fat to sit on. Think about that," he grinned.

He got up to pour somebody some more coffee, came back to the table and continued his train of thought without hesitation.

"Anatomy, nature, art, craftsmanship, and chairmanship - they're all related.

"The chair, for instance, is based on the shape and function of the buttocks.

"I have made a study of chairs," he paused and grinned, "and I have also made a study of buttocks. But back to chairs.

"Consider all the different styles, sizes, and shapes of chairs; the thousands of vogues and extravagances in chairs since the dawn of history. Big, little, fancy, plush, adorned, thrones, stools, upholstered; plain wood, metal, plastic.

"Look at the over-stuffed easy chairs millions of men plop into with a beer can to watch TV football. Compare those to the austere ladder back chairs lovingly crafted by our forefathers."

He would look around, his eyes sparkling, a cigarette dangling from his fingers.

"The chair is the most important piece of furniture we have because it elevated us off the ground." Then, immediately, before anyone else, he would see the incongruity of what he had just said and quickly add, "Hell, the bed does the same thing, maybe better. But the chair - the chair is the seat of Western civilization!"

Those gathered around would laugh at his pun, and Burkhart, before drifting to another topic, would screw up his face and say, Ah, hell, there's so much to learn and so little time to learn it in."

Another time, another conversation - someone else was there, maybe two or three people, but I can't remember who they were. We had been walking from room to room through the large 19th century house. Burkhart was doing most of the talking and, finally, we arrived in the back living room.

Like a lot of people&emdash;make that most people - especially as they get older, Burkhart had his favorite stories and anecdotes he would trot out and, from time to time, I would hear more than one version of the same story.

On this occasion. I remember he dropped down on a brocade sofa, talking as he descended, and the subject on his mind was children.

"The child," he said," the baby when it is born, is a lovely creation. It is beautiful and innocent and over a period of time, we mold its Psyche into the person it becomes as an adult.

"Its parents do this, the teachers in the schools, the newspapers, television and books; the real estate man, the shopkeeper, the policeman, the lawyer, the judge, the church people - and, of course, its own contemporaries.

"Picture it," he would say, "all of them chipping away at this tiny bit of sculpture," and his hands swept through the air.

"Some handle it gently, smoothly and caressingly - with great love, He continued.

"Others hack and slash at it viciously.

"But for better or worse, eventually there emerges the finished product.

"Each little person, each individual as they finally emerge - like butterflies from a cocoon, or autos from an assembly line - could be stamped 'Made in America.'

"Thousands of people have had a hand in it. Collectively, we pass on our knowledge, our loves, our hatreds and our prejudices.

"If we have many failures, it is because we have failed." His face would be serious now, his pale blue eyes crisply intent.

"How many beautiful adults are there? How many do we produce?

"I don't mean plastic beauty. I mean beauty of the soul, a beauty that literally shines out from a person. That kind of beauty represents the highest achievement of nature - and mankind.

"There is a difference between a beautiful woman and a lovely woman," he grinned. "A beautiful woman, one beautiful of face and body, can have a paltry soul, she can be mean and petty, a shrew; in her mind, the whole universe centered between her legs, or whirling around her inflated ego.

"I made love to such a woman once and it was like making love to the back side of a mirror." Laughing, he stopped to light up a cigarette, took a puff, and picked up the thought where he had left off.

"She was madly in love with herself. How could she be in love with anyone else?

"I was an intruder. Gawd, I disliked her. I wanted to go off like an atom bomb - just to see if she would move.

He grinned broadly. His hand ruffled his white thatch of hair until it took on the appearance of a bursting milkweed pod.

"Of course, most women when they make love concentrate very intently on themselves. On the other hand, the mind of a man wanders. He's an incurable romantic. His mind is weaving a sexual tapestry of color, sound, fragrance, texture, and visual experiences. He is embracing the world and he explodes in a psychedelic abandonment of self.

"That's why they say a man comes closer to death, in a figurative sense, at the moment of climax than at any other time in his life. Since birth is the opposite number to death, maybe the woman is closer to the beginnings of life. Literally and figuratively."

Getting up from the sofa, he stretched, and concluded his conversation with the remark that life was a complicated business.

"There's so much we don't know," he said.

In the next episode, I will tell how Emerson and I visited a famous brothel, right here in Columbus.

Part IV

In between his jabs and jibes at the human race ("It comes naturally," he would say, "I'm an Aquarian."), Burkhart painted day in and day out with a determined consistency.

I suppose he would have said that it was his job, so why shouldn't he? Just as most people fulfill their obligations to make a living, he would pick up his paint brushes and go to work.

Lucky for him, it was work he dearly loved. Part of it, I would think, was the freedom of the mind it offered, plus the Henleyesque opportunity to be captain of his own soul, not to speak of enjoying his great talent in being able to transform pigment into whatever his imagination commanded.

Sometimes he wandered out into the countryside to paint, but mostly he wielded his brush around the city, painting everything from junkyards and old railroad locomotives to models and cadavers. This was especially true for the many years that his paintings were uncompromisingly realistic.

"Hell," he would say, "beauty is everywhere. A pile of horse manure can be beautiful if the sun is shining on it just right! But a lovely woman," he would quickly add, "is the most beautiful thing in the world!"

In addition to all the before-mentioned subject matter, Burkhart painted his own portrait with regularity, and this might be the trait that eventually endows him with the most fame.

How many self-portraits he painted, he could never remember, but they must have numbered over two hundred.

"It's cheaper than hiring a model," he would say, "and it's reliable. It's always there when I want it."

The remarkable thing about all these self-likeness was that no two of them were alike. Far from it.

What he had undertaken was to paint all the universal traits of humanity, sometimes throwing in a profession or trade if it seemed to strengthen the characterization he had depicted.

There was Burkhart as a lovable old fisherman, while another, titled "Materialism," showed a money-grubbing lecher clutching a handful of greenbacks.

"Faustian Man" is a portrait of asociopathic ego-maniac, while "The Animal Nature in Man" humorously portrays a self-satisfied individual contentedly scratching his chest.

Thousands of people attended the open houses he held over the years. He would have paintings hanging everywhere and crowds of people would elbow their way through virtually every room of his 22-room house on Woodland Avenue.

In the middle of the milling crowd was Burkhart, a happy smile pasted on his face, posing for TV cameras, quoting prices on paintings, saying hello to one and all.

The open houses were a response to a supposed snub he received at the hands of a visiting jurist for a show at the Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts. In other words, none of the paintings he had submitted were selected for the show. The juror liked modern art. No crime there. As any artist will attest, you can't be on the bandwagon every time.

That didn't wash with Burkhart so he had his own show. That first open house received more newspaper publicity than the highly-touted show at the Gallery.

That first year set the pattern. An open house every year and always lots of media attention, frequently on the front pages of Columbus' two leading newspapers.

So many people would attend that on one occasion someone had to call a deputy sheriff to direct the traffic out on Woodland Avenue.

He was opinionated. No doubt about that. He didn't like abstract art. He revered the great masters of the Renaissance.

His dissatisfaction with the state of the arts widened to include a running feud with the OSU art department

What would happen was that in some interview or other Burkhart would complain about the prominence and acclaim given to modern art and some faculty member would rebut his argument in the papers or on TV. In all truth, listening to him denigrate almost all modern art could become very tedious.

Later, he would change his views somewhat as his work evolved into a self-described lyrical period.

Burkhart once painted what is said to be the only portrait from life of Carl Sandburg.

The famous author/poet said of him: "He knows cornfields and prairie people and the drift of intention therein."

The painting hung over the mantle in his study and to anyone who asked he would tell them it wasn't for sale.

One summer afternoon I stopped by Burkhart's house to say hello and he greeted me with a big smile and asked if I wanted to go with him to Margaret's.

"Who is Margaret?" I asked him.

"You don't know who Margaret is?" he grinned at me. "Well, for your information, Margaret runs the neatest little whorehouse in Columbus.

"You're kidding!" I replied with a sound of disbelief in my voice.

"No, I'm not," he said, as he picked up the telephone. "You know I wouldn't kid about something that important."

I watched as he dialed the phone and then listened for a voice on the other end of the line.

"Margaret? Hi, it's Emerson. If I bring a friend over in about half an hour, can you fix us up with a couple of the most beautiful girls in the world?"

"You can?! Great! You're a genius! We'll see you shortly, dear."

I still couldn't believe my ears, but shortly afterward, we were off to see this lady with a little black book. As usual, we both drove. Some kind of male thing. Emerson was driving his red convertible; I was following in my whatever-I-was-driving-at-the-time.

Margaret lived on East Town Street or Bryden Road. For the life of me, I can't remember which. And since I was only there once, I doubt if I could remember the address even if I was hypnotized.

But I'll tell you this, I don't have any repressed memory syndrome about what happened over the next hour or two.

Part V

To Madam Margaret's we were going, Burkhart in his sporty red convertible, me following behind in whatever-I-was-driving-at-the-time.

I pulled up behind him as he parked his car on Bryden Road - or was it East Town Street? I dunno. It was so long ago, I forget.

We were in front of a respectable looking duplex and I followed him up a flight of steps to a door.

Burkhart knocked and we waited for a few seconds before it was opened. I was a little bit apprehensive. This was a comparatively new experience for me. What I mean is visiting a whorehouse in Columbus, Ohio.

The door opened and there was Margaret! Voila! Beaming, conser-vatively well-dressed, looking like the All-American mother. She threw her arms around Burkhart, gave him a hug, nodded in a friendly manner to me, and asked us in.

When Burkhart introduced us to each other, she held my hand in both of hers and I felt more than ever like I had met an old friend or relative.

As she showed us into the living room which was tastefully furnished in Victorian-style furniture, I immediately recognized a Burkhart painting on one wall.

I decided to be discreet and not say anything, but in the back of my mind I was laughing and wondering if he had been working trade-deals with the house.

My thoughts were interrupted by Margaret asking if we would like highballs while we were awaiting the arrival of the girls.

As we sat sipping our scotch and sodas, I learned that Burkhart had known Margaret for years, that they had gone to high school together. Emerson said that Margaret had been voted the girl most likely to succeed in business.

I asked Margaret if she had ever been arrested or busted. "Heavens no," she replied.

"I have the best clientele in Columbus," she said. "Top businessmen, judges, lawyers, politicians - and, how can I say this nicely? Well, I'll just say, gentlemen of the cloth - and prosecutors, architects, artists even. She winked at Burkhart who was sprawled in an easy chair, sipping his drink.

For my part, I couldn't believe what I was hearing. In the meantime, Margaret had gotten up, gone to a hall closet and come back with a handful of whips.

"The cat-o'-nine-tails is what some of them enjoy," she said, especially the judges and the clergymen."

She had selected the little whip she had mentioned and playfully swished it through the air.

Burkhart cracked that he liked his sex like eggs, sunny side up, and Margaret and I laughed at his droll humor.

For my part, I was learning anew one of the great lessons of life, simply put, the colossal hypocrisy and deceit of many human beings.

Just then the phone rang. Margaret picked it up, chatted for a few seconds, then her face fell.

When she hung up, she said that she had some bad news.

"I'm afraid neither girl can make it, she announced. They both have bad colds and they don't want to give them to you."

She rolled her eyes. "Not only that, I'm sure you boys understand, they just don't feel good."

We said that we understood and, like a couple of sycophants, nodded our heads sympathetically.

"That was real thoughtful of them," Burkhart said with a smile. "We sure wouldn't want to get their colds." There was a trace of sarcasm in his voice.

With that we finished our drinks, said good-bye to Margaret and as we were going down the steps I remember Burkhart grumbling that they ought to find a cure for the common cold.

Out in front, I said good-bye and went on my way. Sort of relieved. Sort of disappointed.

As I drove home, I recalled other adventures, other conversations with Burkhart.

He used to send me letters from all over the world, excerpts of which I would print in Columbus Magazine, which I published. That was when he was traveling with Carl Jaeger's International School as artist in residence and father confessor for the students, compliments of Carl.

The school was founded by Jaeger and each year he signed up a couple dozen kids just out of high school for a nine-month jaunt around the world.

The students would live with residents and be taught by nationals as well as by staff teachers.

A typical itinerary would be: Tokyo, Hong Kong, Bangkok, New Delhi, Athens, Rome, Paris, Berlin, London, and the Canary Islands.

Burkhart went on two or three of these excursions. Not bad for an artist befriended by a millionaire educator and art collector.

"I lived on a farm until I was twenty," I remember him telling me.

"Followed a plow, that's what I did. Always glad that I spent my youth in the country. The farm gives you a rich background. Better, I should say, than living in the city."

Once, in a lengthy letter Burkhart wrote: "When I was in the first grade, I drew a likeness of my teacher on the blackboard and they called me an artist. My father's suppressed desire was to be a lawyer and that is what he wanted me to be.

"I enjoyed literature as a young person and he used to criticize me for reading poetry and stories about the great artists.

"He sent me to Ohio Wesleyan University and insisted I take public speaking and law. He said, 'After you get four years of that under your belt, you'll forget about artists and drawing books.

'Only one in a million makes it in art. But the study of law leads to business administration, politics and law itself.'

"So my question was: How can I tell if I am that one in a million if I don't try?

"I went to Provincetown, Mass. where there were lots of artists. I met Eugene O'Neill there and a lot of advanced art students.

"I was a farm boy who was very naive. I didn't know how to put a nickel in the subway turnstile. Didn't even know who O'Neill was at first. The boys I was with were more learned than me. They would talk about Faust. I had never heard of him.

"Then I spent four years in New York City studying art. For two years I did abstract painting with a group of artists there in New York. They were three years ahead of anything Picasso did.

"I painted a view with a tree, with blue water in the distance and two people in bathing suits walking toward the water, and a young Jewish girl said, 'My God, when you can do this kind of painting, why would you do those other things?'

"It didn't take me long to make up my mind that I had to paint something that was closely related to human life - with bare feet on the ground.

"If I had kept at non-objective poses, I would have been nuttier than a fruitcake and I would have lost my mind.

"I think the essence of human life never changes. There are only so many kinds of yellow and so many kinds of blue. There are so many summers and so many winters.

"I can find beauty in a pile of horse manure if the sun is shining on it just right.

"Once when I was painting in a junk yard, I saw a rusty pipe with the sun shining on it. It has as great a beauty as the crown jewels of England. It was a beautiful thing.

"I am an optimist and I think this world four thousand years from now will be better than it is now. With all the ups and downs, war and peace, living then will be an even greater experience than now.

"I love the colored race. They are more expressive and they have fewer inhibitions. I love them. They are emotional. They don't worry too much.

"I can foresee the day when we will all be integrated and for the better. I have seen many colored women that I would lots rather live with than a lot of white ones, but society prevents that, but in the future that will take care of itself."

"My father lived to be 77 years old. I showed him a $4,000 painting. He was materialistic in a certain sense and he asked, "Can you sell it?"

"I showed him the check for $4,000 and, I do believe - though he wouldn't admit it - that what I was doing was an easier way to make a living than raising corn or pigs.

"I have never thought of myself as a materialist. Francis Bacon said this about money: 'Great wealth is a handicap and great poverty is a handicap. Somewhere in between is best.' I kind of go along with that.

"A person is influenced by every person and every book they read.

But most people don't read enough. Not nearly enough, and not early enough. Most people's minds deteriorate right along with their bodies. It's very depressing.

"You can hardly talk to most people about anything worthwhile. All they can do is gossip. That's what they are best at. And, that goes for men, too. Their minds are garbage dumps. Dirty jokes, gossip and sports. Then back to sex.

"My head would come off if I saw more than two adults downtown carrying a book. Amend that. Carrying a worthwhile book.

"I make this statement. A number of years ago my late wife and I went to the Chicago Institute of Art to see a collection of paintings loaned to them by the German government - master works by Franz Hals, Michelangelo, etc.

"In the same institute they had a show representing 200 years of American painting. Later, we went through and saw that.

"To put the ten greatest American paintings of the past in with the works of our predecessors . . . they are pretty puny. The greatest Bellows hung beside a Velasquez.

"American art is in the future. There is little mural art in the United States worth contemplating. America must waken to a greater appreciation of all the arts. And the sciences! How confused, how disinterested we are!

"And just because you are interested in the space program and you and fifty million other people watched John Glenn orbit the Earth - don't think you know anything about science.

"Read, read, read.

"Discuss what you read with those few people that are also interested. Read up on anthropology and the biological sciences. Study history. Read philosophy.

"How people can be so utterly conceited as to even express an opinion when they don't even know what they are, where they've been, where they are, or where they are going is beyond me.

"We need to wake our minds up!

We desperately need to kindle the love and appreciation of the gentler things in life.

"We desperately need to understand and love our fellow men, all over the world.

"If we don't, watch out!

"We will become about as nice a group of people as a bunch of ingrown toe-nails."

Part VI

In conversations with old friends, acquaintances - and sometimes strangers - Emerson Burkhart's mind would ricochet from one idea to another.

His hair always seemed to be tousled, as much a trademark as the scratchy, wry grin on his face.

The concepts he discussed, penned in letters, and endlessly recorded in dozens of journals, encompassed the entire human experience.

He was an avid reader. His library was jammed with hundreds of books on many subjects. Books that were of particular interest were apt to be dog-eared and copiously marked and written in along the margins. He could recite poetry and passages from Shakespeare through the night, but he was seldom pontifical, and friends and acquaintances marveled and loved him for his prodigious memory.

Once, when he was a teenager, he went camping in the Everglades with some other boys.

"One night, in our tent, one fellow must have told a hundred filthy jokes," he remembered. " I thought to myself, his mind is really organized to remember all those dirty stories. Well, for every joke he can tell, I'm going to learn a classic masterpiece."

He made good his promise, and then some. But he was no prude. His language could be exceedingly colorful and his subject matter often took him out on thin ice. He just didn't waste his time remembering off-color stories.

The greatest poems are still to be written, he would often say. The most sublime paintings are still to be created in the future. How does one maintain enthusiasm for life, for deep, honest, sincere work? he would wonder. What is the secret of man's drive, whether he be a contractor or architect, artist or poet, or laborer, or whatever, in this Big-Freedom-Loving-America?

"I think sometimes when love dies down, enthusiasm for almost everything else connected with life dies," he once wrote. "How can one sustain the ability to grab enthusiastic sparks of life and forever keep the fire glowing? Humanity, love of people; to be able to cause a smile instead of a frown, to generate enthusiasm instead of despair - these are the qualities we all need."

Yet, like Heraclitus, he could argue the reverse side of the coin. "The Chamber of Commerce mentality gets boring too," he would say." Life, like in all great literature - which is simply a reflection of life - must have its tragic side. Everything has its opposite number: light and dark, health and sickness; wealth and poverty; love and hate; passion and apathy, the list is endless. There has to be a compromise; a path to walk in peace and serenity." Then he would shrug his shoulders and grin. "Nobody really knows," he would say.

A lot of things happened to Burkhart during the last twenty years of his life. Some good, some bad. His wife, Mary Ann, died in 1955, the same year that his only brother, Paul, died when he fell out of a haymow and broke his neck.

Thinking of Mary Ann, he would say, "She was the most beautiful woman I ever saw in my life. She was only a girl when I first met her, probably about 15. I was much older and we didn't marry until much later, but she left an impression on me I've never erased from my mind."

In a perceptive and compassionate assessment of Mary Ann's role as wife, Burkhart reflected that "she not only loved art, she was the best and most understanding wife an artist could ever hope for."

One curious thing that perplexed him, however, was the fact that she - like a number of women - had foretold an early death for herself.

When that came to pass when she died of cancer of the liver at the age of 37, Burkhart's grief was convoluted by those self-same prophesies she had voiced.

"I just can't stand women who say they're gonna die young," he said. "If they believe it, they will."

Before she married Burkhart, her name had been Mary Ann Martin, the daughter of a south side druggist. She was captivated by all of the arts, and she was equally attracted to people of an artistic temperament.

In New York, she had modeled for a number of outstanding artists including Edward Hopper, Kuniyoshi, and Eugene Speicher. At one time, she also modeled for art classes at OSU.

Mary Ann was a writer. She wrote at least one novel, and a number of shorter things, all evidently unpublished.

After her marriage to Emerson, they settled down in Columbus, bought the house on Woodland Avenue, and she enthusiastically made a career of looking after him. This meant running the household, managing his appointments, seeing that he didn't work too hard, and creating a pleasant social life, including entertaining at home.

The deaths of the two people closest to him was hard to take. They had been the only family he had. For a man with his strong outgoing tendencies, there was only one recourse left, he - more or less - adopted the whole human race.

A peculiar thing happened in the aftermath of that year. From painting greatly detailed, dark canvasses often preoccupied with the macabre, he suddenly changed his subjects and style to brightly colored scenes and landscapes, most of them done in a matter of hours, all of them capturing lots of light and executed in a more impressionistic manner. He called this his lyrical period. It lasted until his death.

Burkhart never remarried but he loved women and women loved him. If he didn't charm them with his ready wit and percolating personality, he would awe them with his storehouse of knowledge.

There was the young schoolteacher he met in England - a few months later she hopped a jet to Columbus - and stayed for over a year.

Two TWA stewardesses staying overnight at an airport motel heard about his Open House. They hopped into a cab, arrived at his house about 10 pm, enjoyed themselves thoroughly, and ended up in one of the famous late, late conversationfests in the kitchen.

About 2 am, one stewardess turned to the other and said, "When you get to the motel, have the cab bring my bags back here. I'm not flying out tomorrow." She didn't fly out for many months.

This, then, was the man Burkhart.

Carl Sandburg said of him: "He knows cornfields and prairie people and the drift of intention herein." (Burkhart did the only portrait from life of the famous author-poet.)

From his notebooks, letters to friends, and interviews, he left behind a legacy of pithy wisdom:

"All human beings are lonely. You are either lonely or something worse - tied to somebody who makes you wish you were lonely."

"You can't educate most people. They're like sheep. The bell rings and away they go."

"Truth shocks people. They're so used to hearing falsehoods that when they hear the truth, they can't believe it."

"An artist would make a good president. Better than a lawyer or a politician. An artist would be constructive and he would create order and beauty.

"Science doesn't impress me. H-bombs, super-jet airplanes - the thing that impresses me most is that little machine in the top of a person's head that is responsible for these gadgets.

"The biggest brains that have ever been put in the top of homo sapiens' haven't improved much to this day. I mean from Socrates and Diogenes to Bertrand Russell. None of them know the origin of life, or its purpose. Me too!"

"Love is the moving force in the world. Everybody should remain constantly in love. Wouldn't it be fabulous! Love isn't a faculty of youth alone. It's a human quality that need not ever end. I've been in love 700 times. Heck! I can't look at a beautiful woman without falling in love."

"We've got to tune this old world up so everybody plays the fiddle!"

"Like old Walt Whitman said, 'Healthy, free, the whole world before me. The little path leading wherever I choose to go. I ask not good fortune. I myself am good fortune.'"

"My weed-filled back yard is more beautiful than those houses with five acres of mowed lawn."

Prophetically, not too long before he died, he jotted down the following lines:

"Death is a blessing, a peaceful sleep, an earthly organism's usefulness over. Living is nervous souls, eyes, bellies, and millions of organs working in conjunction with all nature. I have seen that it's heaven and hell. It's everything and it's nothing. It's pain, greater grief than Job's, hate stronger than Melville's Ahab, and love as serene as Poe's Annabel Lee."

(to be continued)

Part VII

In the kitchen of his old house on Woodland Avenue, tousled, scratchy, a wry grin on his face, Emerson Burkhart would entertain friends and visitors over cups of hot, black coffee.

At such times, he would play with ideas like a cat stalking a mouse, nipping and teasing before sinking his teeth in for the final kill.

He was fond of lambasting the world (a lover's right, he would say). Fingering a cigarette as he talked, eyes narrowing through the smoke, he would take on any subject - from world peace to the problems of racial harmony to styles of painting, to how a man can best get along with or without a woman.

Likely as not, there would be a pan of cold Pettijohns (his favorite cereal) on the back burner of the stove. An assortment of small paintings hung on the wall. The light switch panel was painted in a sunburst of bright colors.

Gesturing, he might say, "There is enough beauty just in Ohio for me to spend my entire life painting here."

Then, a week later, with Karl Jaeger and the students of the International School, he would flee to the Canary Islands, to Athens, Rome, Paris, London, and temperamental, sunny Spain.

As he toured the world, he painted up a storm. He painted people and he painted places. When the canvasses were dry, he would roll them up, insert them into cardboard tubes and mail them home to Columbus.

When he was home, young people and students would often tour the house, gather around the kitchen table for a talk-fest.

Sometimes he would shock them with ideas and concepts they seemingly had never managed to articulate.

Oftentimes they would see the wonder of his words, smile self-consciously, sit quietly in their chairs hanging on his every word.

He would tell them he had painted 400 self-portraits, each depicting a trait of mankind, from love to hatred, from poverty to greedy affluence. "It's cheaper painting my own face than hiring a model," he would say.

In several paintings, he would tell them, he painted an old man's confused pleasure at playing cards, or fishing, or just lazily scratching his crotch.

He would reinforce many of his arguments with quotes, ranging from American statesmen all the way back to the ancient Greek philosophers.

He would speak of the characterization of form, the nature of texture. His eyes would sparkle as he talked about women: "the classic beauty of face, the exquisite shape of the female body."

He would talk about the bad blood between nations, races, different cultures, and life-styles, cannily suspecting religion, atheistic in the way of Robert Ingersoll and Clarence Darrow. He despised modern art, and he loathed gushy, pious women.

As he grew older, he undoubtedly grew more set in his ways. He was a staunch Republican, but a small "d" democrat. His friends ranged from the poor to the rich. One evening he might have supper in a small cafe on Mt. Vernon Avenue, the next night dine sumptuously in a Bexley mansion.

Physically, he was of medium height, probably about five feet seven and rather slight of build. He had a wry grin and inquisitive pale blue eyes. As he aged, his riotous sandy-brown hair took on the appearance of a bursting milkweed pod.

One thing is sure. He died entirely too young. When he suffered his fatal stroke in the autumn of 1969, he was only 64 years old. Anymore, that's middle-aged.

His death was our loss. Who knows what beautiful and interesting paintings would have materialized from his brushes had he lived another 15 or 20 years?

Sometimes Emerson and I would talk about death because in our lexicon dying was a natural thing, the price of having lived, you might say, the death W. C. Fields was talking about when he called him "the fellow in the Bright Nightgown," the state of existence that Annie Dillard delineated so clearly: "The terms are clear: If you want to live, you have to die . . ."

At such times, he would wrinkle his brow, take a puff on his cigarette, look me straight in the eye, and say:

"I've traveled all over the world and there are a lot of beautiful places, but when I die I want to be cremated, and I want you to scatter my ashes somewhere up in Delaware County.

"I've fished and I've painted up there and, y'know, it's just as pretty as anywhere else."

Then he would say: "Someplace along the shore of Hoover Reservoir would be just fine."

At this point, he got a mischievous grin on his face. "Y'know, that's part of the city water supply and no matter how much they sift and strain it, a little bit of me will end up in half the people in Columbus!"

According to his wishes, that's what we did.

Karl, his friend Helena, and I scattered his ashes along a picturesque stretch of shoreline in the vicinity of the Oxbow Road boat ramp.

That was in November, 1969. If Columbus experienced a renaissance of the arts during this past quarter century, you now know the reason why.

The conclusion to this story is rather difficult for me to relate because, as a rule, I do not believe in the supernatural.

The following July I had taken my canoe up to Hoover and with a companion put it in the water at the Oxbow Road boat ramp.

We leisurely paddled across the wide upper end of the reservoir to the "Grand Acres" area, south of Galena, poked around through the little inlets that line that part of the shore. We ate some lunch we had packed, watched a Green Heron as it intently searched for his, then we headed back toward the other side.

I set my sights on a point of land very close to where we had scattered Burkhart's ashes.

The sun had set and darkness was closing in; there was no wind at all, the water was perfectly smooth, the color of old pewter. There were no fishermen along the shore and the last boat had long since disappeared.

I adjusted our course so that we were heading straight for the spot where Karl, Helena, and I had said good-by to Emerson.

As we glided into the darker shadows of the tree-lined lakeshore, perhaps 100 yards away, a strange and awesome thing happened. The water along the shore leapt into the air.

Dancing at least three feet or more upwards, frothy and white, it spewed forth along 15 or 20 yards of the shoreline - exactly where we had scattered Emerson's ashes.

Flabbergasted, we put our paddles down and let the canoe glide closer to the cascading water.

Suddenly, it stopped, maybe when we were 25 yards away. The duration of the phenomenon had been no more than 40 to 50 seconds. A short time perhaps but, on the other hand, immeasurably long.

When the canoe finally nosed against the shore, there was nothing there but a bit of froth and foam.

It certainly would make a better story if I were to surmise that perhaps we had found a loophole there at the water's edge, a momentary parting of the curtain that had allowed some communication to pass through.

I don't believe that for a moment. There were natural causes for what we witnessed. Of that I am sure. And Burkhart would have been the first to agree.

At any rate, I have come to the end of my story about Emerson Burkhart, an extraordinary man and a splendid artist.

Just before his death he had a conversation with Mahonri Sharp Young, Director of what was then the Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, regarding an all-Burkhart show.

He didn't live to see that dream fulfilled, but the show was held the year after his death. One hundred sixty of his paintings occupied seven gallery rooms and attracted large crowds.

His paintings hang in the Smithsonian; The Butler Art Institute, Youngstown, Ohio; the Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, Virginia; The Columbus Museum of Art; the Dayton Museum of Art; Franklin University; Capital University; The Ohio Historical Society; The Ohio State University, and in numerous private collections.

THE END

Return to beginning of article