Columbus, Ohio USA

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com

Jack Sensenbrenner, A Straw Hat and Spizzerinctum

by Betty Garrett Deeds

April 2003 Issue

Return to Homepage

Return to Features Index

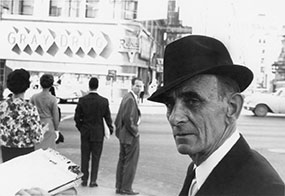

Jack Sensenbrenner, October 1963 Photo © Tom Thomson It's hard to believe it's been 32 years since Jack Sensenbrenner left Columbus' City Hall, after presiding a record total of 14 years as its mayor (1954-60) and (1964-72). Harder still to realize that there are some young people and newcomers to Columbus who may not remember (nor even have heard of) the skinny, sassy politician who was a cross between Harold Hill in The Music Man and a deceptively sharp leader who brought about lasting changes to this city while he maneuvered them like peas in a shell game.

No matter who has occupied the office since – how badly or how well – when he left City Hall, its atmosphere lost something that has never been replaced. Jack Sensenbrenner had a quality he called "Spizzerinctum," claiming it was what made him and "Columbus, the United States of America, the Boy Scouts of America" and possibly God Himself "absolutely DY-NAMIC!" Unless it was winter, he usually doffed a straw skimmer from his head at that point, rolled it around in his hand and did a shuffle that would have been the envy of any vaudevillian who ever lived.

That included Ted Lewis, the legendary vaudevillian ("Me and My Shadow") who made Circleville, Ohio, famous before Maynard E. Sensenbrenner and his twin brother Marion were born there on September 18, 1902. Their father, Edward Sensenbrenner, was a jeweler, and their mother a loving woman who used to wheel both boys around town in a big wicker buggy. "Kids never forget those kindnesses," Jack once winked.

As a boy, he returned that favor by "spending many a day picking peas for 5 cents a bucket," adding, "and my mother got the nickel." It's appropriate that he became a Democrat, because in grade school, he showed an early fondness for donkeys. He was often photographed on a jackass paraded around Circleville to immortalize the town kids. That's how Maynard E. became "Jack," who added quickly, "though my friends left off the rest."

Years later, after he became mayor, he admitted that he had carried youthful ambitions. "I decided a long time ago I was gonna go out and build me a world, and that was it," he said. But there was no sign to others in high school that he would do anything important. In fact, he joked, he was voted "Most Likely to Hang," and "gave those teachers the terrors."

But he was active in the Boy Scouts, and decades later still carried several folders of his medals, explaining proudly, "I've been a Silver Beaver for years – that's the highest layman's rank in the Boy Scouts. I also got this one that says "Every Scout to Save a Soldier" for selling the most (World War I) stamps." However, he already exuded a restless "dy-namic" energy that got him involved in activities of all kinds, except the ones many teenaged boys gloried in.

He didn't make the Circleville High School football team because he was "only 140 lbs. with wet sponges on both feet," but he "got a letter for carrying water for the team." It was also from the football coach Ivan Davis that he picked up the name for a quality that carried him through the rest of his life. "He used to come into the locker room and yell, 'What you guys need is a good shot of Spizzerinctum!'"

Spizzerinctum, Davis explained – but Sensenbrenner immortalized later – is "a quality 1,000 times greater than enthusiasm!" Ever after, Jack admonished others to get a good shot of it, too, and he displayed it himself by living his life in exclamation points.

He needed plenty of it when he fell for "a new girl in town named Mildred Harriet Sexauer." She moved there from Lancaster, where her uncle "was Mayor for years." Did that influence his own ambitions? He never said as much. Mildred claimed that at the time she "didn't pay much attention to Jack." Adding, "You know how it is then. Boys your own age seem younger to you, so I usually dated fellows out of school. Besides, Jack didn't go in for athletics, and athletes were my heroes then."

When senior prom time rolled around, though, she recalled that "Jack was on the seating arrangements committee and he came up and informed me I would be his partner. I guess I had no choice." Later, she found, "Anything he decides to do, he does." After the prom, Jack recalled, he bought her a Coca-Cola which "cost me 10 or 15 cents, but a wonderful romance grew out of that Coke." In fact, he spilled it all over her party dress.

It was their first and only date in Circleville. Mildred's father died shortly afterward, and she and her mother moved to Los Angeles. According to Mildred, Sensenbrenner "never even wrote a letter."

However, several years later, without announcement, he simply showed up at her house. "Saved my money until I got enough" for my first train ride, he said. They married in Glendale in 1927.

He went to a Bible School in Los Angeles (hoping to become a minister as his brother Marion had) "but it just didn't work out." Well, it was the Roaring Twenties, and Sensenbrenner roared through a variety of jobs. He decided "digging ditches is as important to the glory of God as being a preacher," and he worked his "way up in the oil fields from a digger and a pumper until I ran the biggest gasoline still in America."

He also sold ads for the Los Angeles Times and claimed to have tried his hand at police reporting. "Pasadena and Hollywood were my territory," he recalled later. "I bet you don't remember Ben Turpin, the cross-eyed comedian. I hung around the movie studios a lot and met a lot of stars in those days." That may have led to his single screen experience as an extra in the silent film version of Ramon Navarro's Ben Hur. "They paid me $5 just to sit in the Coliseum one day. Who was in the picture? Nuts! I don't know ... but that's all right, they didn't know me either."

Many years later, when he ran for and became Columbus' mayor, a lot of people claimed Sensenbrenner was an actor. He just laughed. "Sure I am. A character actor!"

During the Depression, when he and Mildred moved around from Santa Ana and Costa Mesa, his dramatic abilities and Spizzerinctum helped him become a successful Fuller Brush salesman.

He would quote poems by Ella Wheeler Wilcox and Frances Willard, and since he always had difficulty sitting still, would bounce around with a soft shoe step and "just run the brushes up them old ladies' backs," apparently with great success. "I sold more Fuller brushes than anybody in the West," he said.

In 1934, the couple returned to Circleville to visit his father. Jack got a salesman's job there, but on a weekend jaunt to Columbus, he decided this was "a goin' and growin' city and the place to be." Shortly after, they moved to the west side and it became home for most of their lives. They raised two sons there, Edward and Dick, while Jack was partner in a religious bookstore.

He became involved in community activities on the Hilltop for 19 years, acquiring a reputation as "Johnny on the Spot" while leading Boy Scout troops, teaching Sunday school classes, and giving after-dinner speeches at the Kiwanis Club. He also served on the Ohio Civil Service Commission, but if he nurtured political ambitions himself, it wasn't publicly known until one night in 1953.

Unannounced, he walked into a meeting of the Franklin County Democratic Committee, tilted that straw skimmer he had taken to wearing, and announced without preamble: "The name is Sensenbrenner, and I want to run for Mayor. I hope you'll back me."

The flabbergasted gents sat there in shock and disbelief, probably wondering what had hit them. Columbus was (and still is, largely) a traditionally Republican town. There hadn't been a Democrat in City Hall since Henry Worley rode Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal coattails into that office in 1932.

So who was this wise guy? They didn't know him; so far as they knew, nobody who was anybody else knew him either, and they were looking for someone who might at least put up a good fight in the election before going down in the Count.

Undaunted, Sensenbrenner told them cheerfully, "One with God is a multitude. And besides," he said – and repeated often over years to come – "I got confidence that everyone will be a Democrat when they learn to read."

Well, the Committee didn't have a candidate anyway. Maybe they figured Sensenbrenner would be as good a lamb to drag to the altar as anyone else. No one knows for sure, but at least he was certainly willing. So he got their nomination and set out to wage a "grass roots" campaign of the variety writer A.J. Leibling called "great regional politics. Like sweet corn, it doesn't travel well; it has to be savored on the spot." That was fine with Jack Sensenbrenner, who never had any desire to practice that sweet art outside Columbus.

For the next six months, he set about his campaign rounds at a running walk-and-talk pace, giving as many as 8-10 speeches a night to precinct meetings or any club that wanted a speaker (and lo, they are always with us). He also skipped all around Columbus streets carrying pockets full of patriotic flag pins and key rings, giving them to anyone he could stop, pressing flesh while he expounded on the virtues of Columbus and how he could make it even better. "It's dy-namic – tree-menjus – but why quit when we're just starting to make real progress in this city? We can't just sit around to keep it goin' and growin', which is what I aim to do."

He would tell them about his activities in the Scouts, the Kiwanis Club and his Sunday school, quote the Bible, patriotic slogans and poetry. "Remember, 'A man of words and not of deeds/is like a garden full of weeds!'" He'd tell them about his activities in Circleville, execute a soft shoe and tip that hat while he told them about picking peas for 5 cents a bucket. In fact, people started calling him the "pea-pickin' mayor" during that first run for office.

He also made sure to read newspaper obituaries daily, make a list, then stop to pay his respects to families, most of whom thought it was wonderful that he did that, even if he didn't know the deceased and they didn't know him.

"I fooled everyone who thought I didn't have a chance," he chortled. "They (the pols and the people) never had anyone who went all out the way I did."

It is probable that the critical moment in his campaign transpired one Friday night not long before the election. As chronicled in one of Bob Thomas's Columbus Unforgettables volumes, he walked into the sales offices of WBNS-TV, then at 33 N. High Street, told them his name and said he was the Democratic candidate for mayor. A time salesman there recalled that Sensenbrenner reached into his inside coat pocket, pulled out an envelope full of folded money and explained, "I want to buy 15 minutes of your TV time for this Sunday night at 11:15, right after the CBS News. I think I have enough money here to pay for it."

According to Sensenbrenner, it had been collected by the "church Bible class on the Hilltop, whom I teach each Sunday, so I can tell the people of Columbus who I am and what I will do if elected Mayor."

At that time, politicians (campaigning or elected) rarely appeared on television. WBNS-TV salesmen were glad to see the cash, but uncertain they could fit him into the schedule on Sunday night. They did, though. Richard Nixon probably looked better on TV than Jack Sensenbrenner, but he spent 15 minutes telling viewers all the "dy-namic" and "tree-menjus" things he would do for the city. "I'm gonna build us a world here," he claimed sincerely, concluding, "I hope you will vote for me because I love Columbus and I also love the American flag."

The following week he showed up with the same amount of money and repeated his pitch with even more fervor and Spizzerinctum. It must have impressed some Columbus Republicans as well as Democrats. Come election night in November 1953, perhaps the unlikeliest of all underdogs in the city's history received somewhere between 284 or 327 more votes (accounts varied) than Republican Robert Oestreicher.

They were sufficient unto the day.

Maynard E. "Jack" Sensenbrenner became Mayor of Columbus, and despite predicting his own victory, called it "a miracle!" "40,000 Republicans fainted dead away! But I like every one of 'em," he added quickly, "and I want their votes next time."

Shortly after he took office, the man who was to join vaudevillian Ted Lewis as Circleville's claim to fame, accepted a speaking engagement at one of Columbus' country clubs. "Ladies and Gentlemen," he said sincerely, "I can't tell you how happy I am to be here tonight – because I know if I hadn't been elected Mayor, you never would have invited me."

Yea and verily, that was the truth. Maynard E. Sensenbrenner was not the choice of Columbus moneyed elite and some powerful figures who had never imagined coping with this blunt little fellow whom many of them considered not only a buffoon, but an obstacle to their own wishes for Columbus, which they were accustomed to running themselves in many ways then.

In his first term, he was groping his way through assembling a cabinet of talented and dedicated people who would help him put together "Metropolitan housing" for low-income people and senior citizens; develop a system of first-class parks and recreation centers, and put the Columbus Zoo on the road to becoming a national attraction. In 1960, he lost to Republican Ralston Westlake, but came back in 1964 for three more terms and got the city "goin' and growin" in earnest.

In November 1967, after winning over 70 percent of the vote for a fourth term, he was jubilant but also thoughtful about what still needed to be accomplished. "Listen, I'll tell you how I feel about success. People measure it wrong. It's only when you're broke that you want a chocolate sundae. When you got the money, you're not so hungry. To me, it's working that counts – making life a little better for someone else. If I weren't mayor of Columbus, I'd just be sellin' or something else ... but whatever I do, I try to sow the seeds of something good, of respect for all people."

He eschewed the idea that there might someday be statues of himself outside City Hall, saying, "Heck, no, I never think of myself that way, like history. The American culture teaches us different, see. Europeans are the nostalgic kind who throw up statues all the time."

"I wouldn't want to be one myself. I'd get tired of sittin' on a horse and I don't wanta be a mark for the pigeons."

Concerned about race relations in an era when people were struggling for civil rights, Sensenbrenner operated on the principle that "we just won't change the minds of people who've lived 70 or 80 years with hatred and prejudice, so why argue with them? It's a waste of time. We've got to start with young people, now, right away. It's gonna have to be a matter of education, a thing you can grow natural." He set up a Community Relations Department under Walter Tarpley and encouraged its staff to go out into neighborhoods and "listen to complaints. We'll try to do something about them." Open housing was up to City Council, he contended. "But an Open Door policy starts at my office."

"Boy, I'm not just gonna coast out of here! My biggest desire is seeing recreational plans move and to beautify the entire downtown section too. I'd sure like to see a convention center within the innerbelt, so people from all over the country could come here. Columbus has gotta be alive and vibrant and dynamic ... not just nightclubs, though you needs those too. But we've gotta have a lot of good culture ... you know, opera and all that stuff. Paintings too. I don't understand all those things myself, but they're good for people."

He was a visionary in many ways. Look around.

Sensenbrenner's most tangible achievement, though, was his success at keeping suburbs inside the city, rather than succumbing to urban sprawl.

When he took office in 1954, Columbus was only 41.8 square miles. It had taken 120 years to grow to that point. When he left office in 1972, it was more than 146 square miles, "more than under all the mayors in Columbus history up to that time. It's dy-namic, tree-menjus." How did he do it? "If the suburbs wouldn't come in (annex), I told them I'd shut off their water. And you know how that feels. If you get your water shut off, you're out of luck," he laughed.

By the time he left office in 1972, it, too, had become a unique place that reflected the man himself. He decorated it with antiques and kitsch. Cranking up an old Victrola, he played a record he got for 25 cents at an auction. "How could George Washington Be A Married Man and Never Ever Tell a Lie?" He also dedicated a room to John F. Kennedy, his idol, decorating it with mementos of him and conducting tours to anyone who came there.

It is probable that it broke his heart when he left office in 1972, although he continued to "thank God that a guy like Jack Sensenbrenner could become mayor of a town like Columbus in the U.S. of A." He said he didn't want monuments; he only wanted people to say, "Here was a guy who saw life and helped lift the level of the age he lived in. He didn't just eat, burp and go home!"

Sensenbrenner's grandson, Richard Sensenbrenner, is serving on City Council now, though whether he will ever seek the mayor's office is not yet known. Regardless, no one else can ever take to it the same inimitable personality and Spizzerinctum that only Maynard E. Sensenbrenner possessed.

In 1980, the quintessential Mayor was honored with the dedication of "Sensenbrenner Park" along the river he wanted beautified. A plaque there says it was dedicated to him 'by a grateful citizenry,' and cited his creed: "Love, God and Country Made Columbus An All American City." So, there is a Sensenbrenner Park along the river he wanted to beautify, but no statues of him anywhere.

However, who knows what "shadows" – or maybe even some soft shoe steps – may echo through City Hall at night, after everyone has gone?

Democrat bigwigs, including Mayor Jack Sensenbrenner, greet presidential candidate Robert Kennedy at Port Columbus - Photo © Tom Thomson © 2003 Short North Gazette, Columbus, Ohio. All rights reserved.

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com