Columbus, Ohio USA

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com

Why Old Places Matter

How Old Places Affect Our Identity and Well-Being

by Thompson M. Mayes

TMayes@savingplaces.org

The following excerpts are from Thompson M. Mayes’ book Why Old Places Matter: How Historic Places Affect Our Identity and Well-Being. Subsequent chapters will appear in future issues of the Gazette thanks to publisher Rowman & Littlefield.

INTRODUCTION [May/June 2019 Gazette]

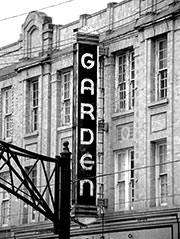

Short North Stage and the rebirth of the Garden Theater are having a positive impact on Columbus’s economy and will support the cultural allure of the city for decades to come. People like old places. They like to live in places like Ghent in Norfolk, Virginia, and Logan Circle in Washington, D.C. They like to live in old houses – in white farmhouses in Vermont, brick mansions in Virginia, and in arts-and-crafts bungalows in Los Angeles. People like to visit old cities on vacation. They like Santa Fe, Provincetown, Mendocino, and Saugatuck. They like Rome, New York, Paris, and Kyoto. They like Brooklyn and Charleston and thousands of towns and cities and countrysides across America and throughout the world. They like ancient troglodytic hotels (Matera, Italy), and Greek Revival houses (Athens, Georgia). They like adobe houses in New Mexico, farmhouses in Ohio, and townhouses in Philadelphia.

Why? Why do people like old places? And why do old places matter to people? Do old places make people’s lives better and, if so, how?

This series of essays explores the reasons that old places are good for people. It begins with what I consider the main reason – that old places are important for people to define who they are through memory, continuity, and identity – that “sense of orientation” referred to in the 1966 book With Heritage So Rich, which led to the enactment of the National Historic Preservation Act. These fundamental reasons inform all of the other reasons that follow: commemoration, beauty, civic identity, and the reasons that are more pragmatic – preservation as a tool for community revitalization, the stabilization of property values, economic development, and sustainability.

The notion that old places matter is not primarily about the past. It is about why old places matter to people today and for the future. It is about why old places are critical to people’s sense of who they are, to their capacity to find meaning in their lives, and to see a future.

I am an unabashed advocate for keeping, saving, and continuing to use old places. Immense and overwhelming economic and political forces cause the destruction of old places at an astonishing pace every minute of every day. We see it in the loss of treasured places both large and small. From the removal of a single, gnarled pear tree that has delighted us with its bloom in the spring and its fruit in the fall, to the inexcusable demolition of public buildings such as schools and churches that give our communities their identity, we are steadily losing our old places. The loss is a soul-destroying severing of people from place, identity, and memory.

There are many critics of the idea of saving old places. Some say that saving old places stifles economic growth and that historic preservation has become too strong a force. They say that preservation is out of balance with the need for change. I see no evidence whatsoever that the forces of preservation in the United States pose a threat to the capacity of the United States to have a vibrant and strong economy. Quite the contrary, old places actually seem to increase creativity and economic growth.

Are there things we should do better? Yes. Are there disagreements among the people who work to save old places?

Yes. Are these arguments about what we retain and how we retain it? Yes. There should be. But the fundamental point remains: the history, memory, and continuity provided through old places are necessary for our self-worth – and are good for people. 11. A note about terminology: I use the term “old places” throughout these brief essays because the term includes not only places that are officially determined to be historic through the National Register of Historic Places or state or local designations, but also the majority of old places in America, most of which are not officially designated. The term also includes places that are not buildings – it captures streets, landscapes, gardens, farms, archaeological sites, cemeteries, and the many other old places that people value. I have also consciously avoided using terms that create an emotional distance between people and places, such as the term “historic resource.”

CHAPTER ONE: Continuity [July/August 2019 Gazette]

Old Places create a sense of continuity that helps people feel more balanced, stable, and healthy.

Churches such as St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church in Victorian Village provide continuity between generations and contribute to the beauty and charm of the neighborhood. Photo © Gus Brunsman III When I ask people why old places are important, a frequent answer is that old places provide people with a sense of continuity. But this idea of a sense of continuity, which so many people obviously feel, is not often explained. What does this sense of continuity mean, how does it tie to old places, and why is it good for people?

Based on my conversations and the research I’ve done at the American Academy in Rome, the idea of continuity is that, in a world that is constantly changing, old places provide people with a sense of being part of a continuum, which is necessary for them to be psychologically and emotionally healthy. This is an idea that people have long recognized as an underlying value of historic preservation, though it is not often explained. In the influential 1966 book With Heritage So Rich, the idea of continuity is captured in the phrase “sense of orientation,” the idea that preservation gives “a sense of orientation to our society, using structures and objects of the past to establish values of time and place.”1 Juhani Pallasmaa, the internationally known architect and architectural theorist, was a resident at the American Academy during my time there, and I’ve been privileged to talk with him about old places. Juhani puts it this way in an essay he wrote: “We have a mental need to experience that we are rooted in the continuity of time. We do not only inhabit space, we also dwell in time.” He continues: “Buildings and cities are museums of time. They emancipate us from the hurried time of the present and help us to experience the slow, healing time of the past. Architecture enables us to see and understand the slow processes of history and to participate in time cycles that surpass the scope of an individual life.”2

We see and hear this idea in the way people talk about the places they care about – in blogs, public hearings, news-paper articles, and anywhere people talk about threats to places they love. Discussing the potential loss of his one-hundred-year-old elementary school, for example, a resident says, “It’s been a part of my life as long as I can remember. ... My great-grandmother graduated in 1917. ... It’s the heart of the community.”

People share stories of the experiences that they, their parents, and other people have had at theaters, restaurants, parks, and houses – as well as events that happened long before their parents were alive. They not only feel the need to be part of a timeline of history, both personal and beyond themselves, but their connection to these old places makes them aware that they are part of the continuum, connected to people of the past, the present, and hopefully, the future.

Environmental psychologists have explored many aspects of peoples’ attachment to place, including the idea of continuity. Maria Lewicka, in her review of studies on “place attachment,” says, “the majority of authors agree that development of emotional bonds with places is a prerequisite of psychological balance and good adjustment and that it helps to overcome identity crises and gives people the sense of stability they need in the everchanging world.”

Although studies relating specifically to old places are limited, Lewicka summarizes the studies this way: “Research in environmental aesthetics shows that people generally prefer historical places to modern architecture. Historical sites create a sense of continuity with the past, embody the group traditions, and facilitate place attachment.”

Lewicka’s summary of one study captures a key idea: “The important part ... is the emphasis placed on the link between sense of place, developed through rootedness in place, and individual self-continuity. Rootedness, that is, the person-place bond, is considered a prerequisite of an ability to integrate various life experiences into a coherent life story, and thus it enables smooth transition from one identity stage to another in the life course.”3Life Story

Life story. This phrase captures the way people create a narrative out of their lives and make their lives meaningful and coherent. Old places help people to create meaningful life stories. This may sound a bit touchy-feely for our American sense of practicality and hard-nosed realism. But the point is that people need this sense of continuity, this capacity to develop coherent life stories, in order to be psychologically healthy.

We can see the importance of continuity in the places where continuity has been intentionally or unintentionally broken. People who have been forcibly removed from their homes, such as those who lived on the land that became Great Smoky Mountains National Park and were removed in the 1930s, described themselves as heartbroken by the forced removal. These former residents continue to visit the sites of their former homes – the remains of an old chimney, the foundation of an apple cellar, and the family graveyard – and to participate in homecomings, such as the one at an old church named Palmer Chapel. Although they had been forcibly removed, the attachment to the place continued and has continued through later generations who never lived on the land but feel a sense of connection to the place.4

On a trip to Puglia, the fellows of the American Academy visited a World Heritage site, Matera, where the residents had been removed from their community during the mid-twentieth century. Our guide at one of the churches, a descendant of one of the families removed from the site, said that her grandmother hated moving and felt that the community never recovered from the forced removal. Studies have shown that the loss of the sense of continuity from uncontrollable change in the physical environment may even cause a grief reaction.5 Put simply, people need the continuity of old places.

Continuity is not, however only about the past, but also about the present and the future. That’s what continuity means – bringing the relevance of the past to give meaning to the present and the future. Paul Goldberger, the architectural critic, says about preservation,Perhaps the most important thing to say about preservation when it is really working as it should is that it uses the past not to make us nostalgic, but to make us feel that we live in a better present, a present that has a broad reach and a great, sweeping arc, and that is not narrowly defined, but broadly defined by its connections to other eras, and its ability to embrace them in a larger, cumulative whole. Successful preservation makes time a continuum, not a series of disjointed, disconnected eras.

Old places help people place themselves in that “great, sweeping arc” of time. The continued presence of old places – of the schools and playgrounds, parks and public squares, churches and houses and farms and fields that people value – contributes to people’s sense of being on a continuum with the past. That awareness gives meaning to the present and enhances the human capacity to envision the future. All of this contributes to people’s sense of well-being – to their psychological health.

Notes

1. Special Committee on Historic Preservation United States Conference of Mayors, With Heritage So Rich (Washington, DC: Preservation Books, 1999).

2. Juhani Pallasmaa, Encounters 1: Architectural Essays, ed. Peter MacKeith (Helsinki, Finland: Rakennustieto Oy Publishing, 2012), 309, 312.

3. Maria Lewicka, “Place Attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years?” Journal of Environmental Psychology 31 (2011): 211, 225 and “Place Attachment, Place Identity, and Place Memory: Restoring the Forgotten City Past,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 28 (2008): 211.

4. Michael Ann Williams, “Vernacular Architecture and the Park Removals: Traditionalization As Justification and Resistance,” TDSR 13, no. 1 (2001): 38.

5. Clare L. Twigger-Ross and David L. Uzzell, “Place and Identity Processes,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 16 (1996): 205-20.

6. Paul Goldberger, “Preservation Is Not Just about the Past,” speech, Salt Lake City, April 26, 2007.Thompson M. Mayes is vice president and senior counsel at the National Trust for Historic Preservation in Washington, D.C. In 2013, Tom was awarded the National Endowment for the Arts Rome Prize in Historic Preservation by the American Academy in Rome and spent a six-month residency in Rome as a fellow of the academy. The essays in his book came about as a result of his experience. Why Old Places Matter was published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2018 and is available at www.amazon.com

CHAPTER TWO: Memory [September/October 2019 Gazette]

Old Places help us to remember.

The Union Station entry arch, the only remaining piece of Columbus' Union Train Station, retains the memory of the original station that once operated on High Street. After the station's demolition, the arch was moved to Arch Park on Marconi Blvd., then to McFerson Commons in 1999 when the Arena District was being developed.

PHOTO | Larry Hamill ©Like many people, my earliest memories are of places – a pasture on our old farm where I napped in the warm sun until a cow licked me and the dining room of my grandfather’s house where we watched President Kennedy’s funeral cortege. Simply seeing a place again may bring back a flood of memories – whether it’s Caffe Reggio in Greenwich Village, which I frequented in my twenties or the Davidson College Library where I pored over architectural history books as a teenager. “Old buildings are like memories you can touch,” the architect Mary DeNadai tells her granddaughter. It’s a succinct explanation of how old places – our homes, libraries, schools, barns, and parks – seem to hold and embody our memories.

Most people experience this connection between memory and place. The connection was acknowledged by John Ruskin, who wrote in “The Lamp of Memory” about architecture, “We may live without her, and worship without her, but we cannot remember without her.”1 But how important are places to memory? Does preserving old places – and the memories they represent – matter? Do the individual and collective memories embodied in old places help people have better lives?

“Memory is an essential part of consciousness,” says Randall Mason, chair of the graduate program in historic preservation at the University of Pennsylvania, talking to me about the large and ever-growing topic of memory studies. Philosophers, psychologists, writers, geographers, sociologists, and historians have written, studied, and theorized about memory, from Proust (yes, that famous madeleine that triggered memories of – what else? – a place) to Freud to French historian Pierre Nora, who coined the term Lieux de Memoire – “sites of memory.”2 Among the thousands of books, studies, and essays on memory and place, many, including Nora, analyze or critique the way memories are shaped or manipulated, including how historic preservationists and others choose what places to preserve and why. Yet even taking into account the criticism of what we preserve and why, most of these writers seems to support what geographers Steven Hoelsher and Derek Alderman refer to as the “inextricable link between memory and place.” Places embody our memories, even when those memories are contested or controversial. As Hoelsher and Alderman put it, “What … groups share in their efforts to utilize the past is the near universal activity of anchoring their divergent memories in place.”3

Places are key triggers for both individual memory, such as those very personal memories I recalled above, and collective memory, the memory shared by the larger society. Diane Barthel, in Historic Preservation: Collective Memory and Historic Identity, captures the relationship between individual memory and collective memory in a discussion of religious buildings: “Religious structures place a specially significant part in the collective memory as places where moments in personal history become part of the flow of collective history. This collective history transcends individual experiences and lifetimes.”4

One need only think about important national sites to see the blending of the two types of memory and how they are tied to place. How many of us remember something both about ourselves and about us collectively when we see the Lincoln Memorial and its reflecting pool or images of the World Trade Center?

People writing about memory have described the mechanisms that drive the connection between place and memory. Places serve as mnemonic aids – they remind us of our memories, both individual (coffee at the Caffe Reggio) and collective (marches at the Lincoln Memorial) – but they also spur people to investigate broader societal memories they don’t yet fully know. Pierre Nora writes, “Memory takes root in the concrete, in spaces, gestures, images, and objects.”5 Environmental psychologist Maria Lewicka refers to studies that discuss “historical traces” and “urban reminders.” As she states, “urban reminders, the leftovers from previous inhabitants of a place, may influence memory of places either directly, by conveying historical information, or indirectly – by arousing curiosity and increasing motivation to discover the place’s forgotten past.”6

Old places seem to trigger memories people already have, give specificity to memories, and arouse curiosity about memories people don’t yet know.

And why is “place memory” important? Earlier, I wrote about continuity – that old places contribute to a sense of continuity that is necessary for people. Memory contributes to the sense of continuity. Memory also gives people identity – both individual identity and a collective identity. As Hoelsher and Alderman put it,

Whether one refers to “collective memory,” “social memory,” “public memory,” “historical memory,” “popular memory,” or “cultural memory,” most would agree with Edward Said [who stated] that many “people now look to this refashioned memory, especially in its collective forms, to give themselves a coherent identity, a national narrative, a place in the world.”7

This sense of identity provided by memory is largely what defines us as individuals and as a society.

Memories and identities are often contested. We see people argue over the meaning of old places – a restored southern plantation house, which may or may not acknowledge the painful memory of slavery, a battlefield that may or may not present the memory of both the victor and the vanquished. People have different approaches about how places should be remembered. They argue over memorials, from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial to the World Trade Center. The history of an old place may be viewed differently over time – and interpreted and reinterpreted as our conception of who we are as a people changes.8

But here’s the key point. The fact that these arguments occur highlights the importance of the place. Regardless of conflicting points of view, the place itself transcends a specific interpretation. The place is the vortex, the common ground, the center point, and the focus where divergent views about memory can be felt and expressed. The continued existence of the place permits the revision, reevaluation, and reinterpretation of memories over time. As Paul Goldberger the architecture writer and critic, said to me in an interview in July, the continued existence of the place “allows new memories to be created.”9 Preservationists often think of historic sites from the viewpoint of significance for architecture or design. Yet architecture critic for The New York Times, Herbert Muschamp, wrote, “The essential feature of a landmark is not its design, but the place it holds in a city’s memory. Compared to the place it occupies in social history, a landmark’s artistic qualities are incidental.”10

People ask, “but won’t the memories survive even if the place is gone?” Yes, memory sometimes outlasts the place. I remember still the smell of the kettle of hot tea on the stove of my grandmother’s house in North Carolina on Christmas Eve, though the house has been gone for many years. Memories can survive if places disappear. But memory – collective or individual – will not prove as durable – nor as flexible – when that vortex of memory, that mnemonic aid, that urban reminder, that historical trace – the old place – is gone.

Notes

1. John Ruskin, “The Lamp of Memory,” in The Seven Lamps of Architecture (New York: Dover Publications, 1989), 178.

2. Nora, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Memoire.” Representations 26 (Spring 1989): 7.

3. Steven Hoelsher and Derek Alderman, “Memory and Place: Geographies of a Critical Relationship,” Social & Cultural Geography 5 (2004): 348.

4. Diane Barthel, Historic Preservation: Collective Memory and Historic Identity (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996), Kindle Locations 1199-1200.

5. Nora, “Between Memory and History,” 9.

6. Maria Lewicka, “Place Attachment, Place Identity, and Place Memory: Restoring the Forgotten City Past,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 28 (2008): 211, 214.

7. Hoelsher and Alderman, “Memory and Place,” 348-49.

8. Since this essay was written, the debates over identity in the United States have intensified and the flashpoints for those debates have often been memorials, especially memorials to Confederate leaders or soldiers. These debates have also extended to other memorials, including Christopher Columbus, Theodore Roosevelt, Junipero Serra, and Juan de Oñate. The National Trust issued guidance about the treatment of Confederate memorials, which read in part: “These confederate monuments are historically significant and essential to understanding a critical period of our nation’s history. Just as many of them do not reflect, and are in fact abhorrent to, our values as a diverse and inclusive nation. We cannot and should not erase our history. But we also want our public monuments, on public land and supported by public funding, to uphold our public values.” See Stephanie Meeks, “Statement on Confederate Memorials: Confronting Difficult History,” National Trust for Historic Preservation, June 19, 2017, accessed February 19, 2018. https://savingplaces.org/press-center/media-resources/national-trust-statement-on-confederate-memorials#.WpLb8Ely74h. The statement was updated after the violent protests in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017. See Stephanie Meeks, “After Charlottesville: How to Approach Confederate Memorials in Your Community,” National Trust for Historic Preservation, August 21, 2017, accessed February 19, 2018. https://savingplaces.org/stories/after-charlottesville-confedrate-memorials#.WpLbjkly74g. These debates suggest just how important historic places and memorials are to people and the way that they can become venues for discussions of our changing identity. Many statues are being moved, recontextualized, or destroyed. From my perspective, these monuments should become the venue and opportunity for discussions that lead to acknowledgment, recognition, and hopefully, reconciliation.

9. Paul Goldberger, interview with the author, July 18, 2013.

10. Herbert Muschamp, “The Secret History of 2 Columbus Circle,” The New York Times, January 8, 2006.

CHAPTER THREE: Individual Identity [November/December 2019 Gazette]

Old Places embody our identity.

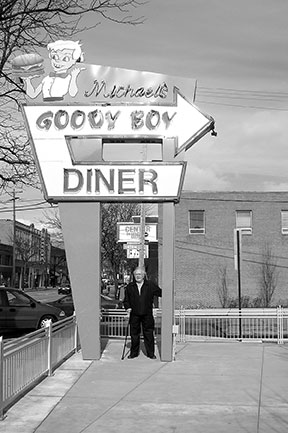

George Stambedakis, standing in this photo, purchased the Goody Boy Diner in 1977 from Michael Pappas and ran it for 23 years before selling it to Jim Velio in 2000. Chris Corso acquired it in 2019. The original sign remains a distinctive part of the community's identity. Photo © Cynthia Rosi “Old places are who we are.” “They give us a sense of self.” “They tell us who we are as a people.” People frequently use these phrases when talking to me about why old places matter. Sofia Bosco, the Rome director of Fondo Ambiente Italiano, an Italian preservation organization, told me, “These places are testimonials of who we are. They represent the identity of every one of us.”1 Old places – our homes and churches, our neighborhoods, schools, main streets, and courthouse squares – are all part of our identity and of who we are.

People have long recognized the crucial connection between identity and old places. In the ancient world, Cicero chronicled the “indescribable feeling insensibly pervading my soul and sense” on returning to the place where he was born and where his father and grandfather lived.2 More recently, architect and preservationist James Marston Fitch wrote that preservation “affords the opportunity for the citizens to regain a sense of identity with their own origins of which they have often been robbed by the sheer process of urbanization.”3

Each of us can probably think of a place, like Cicero’s childhood home, that seems to embody our identity, but how do old places “tell us who we are”? What exactly is this relationship between old places and identity? Earlier, I described how old places are critical for people to maintain a sense of continuity and memory. Identity is closely related to both continuity and memory – they are part of the same package. I’ll look first at individual identity and address national or civic identity in the next essay.

For more than thirty years, psychologists, sociologists, philosophers, and architectural theorists from all over the world have actively studied the relationship between place and identity and have developed a variety of definitions and processes for looking at “place attachment” and “place identity” – how a person’s identity is tied to place. Although there is no consensus about the definitions or processes, most studies accept the notion that “the use of the physical environment as a strategy for the maintenance of self” is a pervasive aspect of identity and that “place is inextricably linked with the development and maintenance of continuity of self.”4

The way places inform our identity and the way we create identity out of place is complex and multiplayered, and there is no agreement about how it works. The Turkish architect Humeyra Birol Akkurt offers a useful summary of a number of other scholars’ definitions of how our identity ties to place:

a set of links that allows and guarantees the distinctiveness and continuity of place in time, . . . the bond between people and their environment, based on emotion and cognition, . . . symbolic forms that link people and land: links through history or family lineage, links due to loss or destruction of land, economic links such as ownership, inheritance or politics, universal links through religion, myth and spirituality, links through religion and festive cultural events, and finally narrative links through storytelling or place naming.

Other writers have noted a sense of pride by association and a sense of self-esteem tied to place. Akkurt notes that one scholar theorizes that for any particular place there are as many different place identities as there are people using that place.5

The Norwegian architect Ashild Lappegard Hauge summarizes a key finding as “aspects of identity derived from places we belong to arise because places have symbols that have meaning and significance to us. Places represent personal memories, and . . . social memories (shared histories).” Hauge concludes that “places are not only contexts or backdrops, but also an integral part of identity.”6

People seem to recognize intuitively the way older places symbolize meaning, significance, and memories. Yi-Fu Tuan, the influential geographer who pioneered the study of people’s relationship to place, wrote, “What can the past mean to us. People look back for various reasons, but shared by all is the need to acquire a sense of self and of identity. . .. . The passion for preservation arises out of the need for tangible objects that can support a sense of identity.”7 Tuan was not uncritical of what and how people choose to preserve and the identities that are reinforced. Yet the fact remains that old places provide tangible support for our sense of identity.

But there also seems to be something bigger at work. It’s not as if we simply decide what our identity with place is. In fact, some theorists say the relationship between place and identity is inseparable. One writer, summarizing the findings of Edward Relph, another geographer who pioneered theories about place, stated, “the essence of place lies in its largely unselfconscious intentionality, which defines places as profound centres of human existence.”8 Or as David Seamon summarized Relph’s idea, place is “not a bit of space, nor another word for landscape or environment, it is not a figment of individual experience, nor a social construct. . . . It is, instead, the foundation of being both human and nonhuman; experience, actions, and life itself begin and end with place.”9

Our place identity is not static, however. It is dynamic. It changes over time. As noted previously, I grew up on a farm in North Carolina. Without any question, my identity is tied to that place – to the frame farmhouse where I was raised, to the cedar trees that line the fences (I can smell the cedar as I write this), to the very quality of the light on the green grass of the cow pastures. I am nurtured when I return to that place. But my identity is not tied only to that place. I also have an identity connected to places where I have lived, worked, or visited – from the leafy green campus at Chapel Hill, to the brick sidewalks and apartment buildings of Dupont Circle, to 1785 Massachusetts Avenue, the former National Trust headquarters, to a 1950s cement block riverside fishing cabin in West Virginia. And I look forward to having my identity further defined, enhanced, expanded, or clarified by Rome and by other places I will know in the future.

Although our identity with place changes over times (and can be re-created in different places), the places that form our identity act as tangible objects that support our identity. Our old places – if they continue to exist – serve as reference points for measuring, refreshing, and recalibrating our identity over time. They are literally the landmarks of our identity.

A place that supports our identity may not be particularly old, although many of them are (or have become so over the course of our lives). Eastland Mall, which opened in 1975 in east Charlotte and was party of my adolescence, was demolished in 2013. Its “rising sun” logo signs are being preserved as public art through the efforts of the grassroots E.A.S.T. community group, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Preservation Foundation, and the City of Charlotte to continue the community memory of a place that was once considered to have “embodied the spirit of the city.”10 The demolition company tearing the building down established a contest for people to share their memories (the head of the company met his wife ice skating at the mall). A man has even had the rising sun logo tattooed on his arm.

I’m glad E.A.S.T. saved the signs, but I wish that more of the place remained. Documented by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Preservation Foundation before its demolition, the vacant building had an evocative beauty that makes me think that the city might have been a richer place in the future if we had figured out how to reinvent the old mall in a way that saved this “tangible object” of my teenage memories and identity. Perhaps our society would be a bit more stable and human – and sustainable – if we didn’t build and replace our buildings every thirty-five years, with the resulting erasure of recent memories and identity embodied in them and the inexcusable waste of demolition.

When the places that are part of our identity are threatened, lost, or destroyed, our identity may be damaged. As indicated previously in the discussion on continuity, when the place is lost, there can be devastating effects on people – a reaction comparable to grief. I grieve for many lost places. I’m sometimes mad about the unnecessary loss – from New York’s Penn Station (which I never even knew), to Chicago’s Prentice Hospital, to my great-grandfather’s gentle white clapboard house.

People survive the loss of places that support their identity. And many times these places survive in memory. But the continued presence of old places helps us know who we are and who we may become in the future.Notes:

1. Sofia Bosco, interview with author, November 25, 2013.

2. Cicero, The Treatises of M.T. Cicero, ed., C. Yonge (London: H.G. Bohn, 1853), 428.

3. James Marston Fitch, Historic Preservation: Curatorial Management of the Built World (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1982), 404.

4. Clare L. Twigger-Ross and David L. Uzzell, “Place and Identity Processes,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 16 (1996): 206, 208.

5. Humeyra Birol Akkurt, “Reconstitution of the Place Identity within the Intervention Efforts in the Historic Built Environment,” in The Role of Place Identity in the Perception, Understanding, and Design of Built Environments, ed. Hernan Casakin and Fátima Bernardo (Benthan E-books), 64-65. https://ebooks.benthamscience.com/book/9781608054138.

6. Ashild Lappegard Hauge, “Identity and Place: A Critical Comparison of Three Identity Theories,” Architectural Science Review (March 1, 2007): 6, 10. www.highbeam.com/docID=1G1:160922464.

7. Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977), e-book locations 2826, 2990.

8. Akkurt, “Reconstruction of the Place Identity,” 64.

9. David Seamon, “Place, Place Identity, and Phenomenology: A Triadic Interpretation Based on J.G. Bennett’s Systematics.” In The Role of Place Identity in the Perception, Understanding, and Design of Built Environments, ed. Hernan Casakin and Fátima Bernardo (Bentham E-books), 5. https://ebooks.benthamscience.com/book/9781608054138.

10. Stewart Gray, Survey and Research Report on the Eastland Mall Signs, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Preservation Foundation, May 30, 2013. www.cmhpf.org/Survey%20Commttee%20Agendas/Eastland%20Mall%20SR.pdf.

CHAPTER FOUR: Civic, State, National, and Universal Identity [January/February 2020 Gazette]

Old Places embody our civic, state, national, and universal identity.

Jamestown. Mount Vernon. Independence Hall. Old South Meetinghouse. Valley Forge. The Missions of California. Fort McHenry. The Alamo. Sutter’s Mill. Harpers Ferry. Fort Sumter. Gettysburg. Appomattox. Little Bighorn. Pearl Harbor. Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. The very recitation of these names conjures the long time line of American History. These places – and countless others – embody the history and principles of the United States. For generations, these places have inspired Americans to learn our uniquely American story.

Just as these places embody an American identity, old places throughout the world embody civic, state, national, and universal identity. Stone cottages with thatched roofs embody Irishness. English country houses and cozy pubs stand as symbols of something particularly English. Temples and Zen gardens symbolize Japan. The pyramids of Egypt and the Parthenon in Greece are valued throughout the world as symbols of our common humanity. Old places help form, maintain, and transform civic identity – whether it’s a city, county, state, region, country, or even the world.

Americans – and people everywhere – care deeply about the old places that embody their shared identity, whether national, civic, or more broadly cultural. They speak forcefully and eloquently about these places when they are threatened. From the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to the Virginia countryside where the Battle of the Wilderness took place, people strive to save these places because they matter to our collective sense of who we are. As the Civil War Trust notes on its website:

Can you image a fast-food restaurant in the middle of Arlington Cemetery? Can you imagine paving over the Vietnam Veterans Memorial? Can you imagine destroying the remaining original copies of the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution? Of course not. But with each square foot of battlefield land that is consumed, whole chapters of America’s history are being ripped out of the book of our national memory, and an irreplaceable piece of our important heritage is lost forever.”1

In America, we’ve had policies to preserve places of national identity for more than seventy-five years, and patriotism and national identity have been key drivers of movements to save old places.2 But we aren’t as single-minded or as uncritical about our civic or national identity as we may have once been. As I listened to people talk about the reasons that old places matter, I noticed that although many people mentioned national identity and patriotism, others were reticent to refer to national identity – or patriotism – as a reason for saving old places. This reticence seems to reflect what American academic and literary critic Edward Said described as the “vexed issue of nationalism and national identity, of how memories of the past are shaped in accordance with a certain notion of what ‘we’ or, for that matter, ‘they’ really are.”3

What is this “vexed” issue of national identity, and how do we responsibly talk about places that reflect our national or other identities? Many of the places we first deemed worthy of preservation were saved to celebrate and promote an idea of a shared American heritage – essentially an American identity. The Daughters of the American Revolution, the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America, and many other state or local organizations saved old places to promote American ideals. These places inspired people about American history and American institutions, while also acting to form an American Identity. The places we sought to preserve represented what we valued from the past. At the same time, they also represented what those who saved these places aspired for America to be.

Countless writers and scholars have criticized the selective choice of what was preserved as part of our national identity, by whom, and for what purpose.4 As someone who has cared about old places for most of my life, I am painfully aware of the exclusive character of many early preservation efforts and the conscious attempts to use old places to tell only a selective view of American history – essentially to define American identity in a way that left out some people or issues. Slavery and enslaved people were not acknowledged at plantation houses. Native Americans were treated as an inhuman enemy at frontier sites. The presence of Irish, German, and Eastern European people was not recognized at a host of places that they built or where they lived and worked. For many years, mill workers, farmers, mechanics, and shopkeepers were not visible in the old places that were preserved as sites of our national identity.

The process of redefining who “we” are is continuous, and today our old places increasingly reflect a more diverse history. Lowell, a textile mill town in Massachusetts, has been a national park since 1978. Steel mills are preserved in Pittsburgh. The reality of slavery is acknowledged at plantations. In my view, it is critically important for people who care about old places to acknowledge the sometimes exclusive history of the preservation movement and to continue to push to have all the stories included in the places that define who we are as Americans. Americans argue vociferously about what our country is, who it is for, and what it means. These debates help reshape and reform and – hopefully – deepen our understanding of history and identity. The old places that embody our identity are the perfect venues for those discussions and debates.

Edward Relph, a geographer who pioneered theories about place, noted when he reflected back on his early work,

I realize that place and sense of place, which I then represented as mostly positive, have some very ugly aspects. They can, for instance, be the basis for exclusionary practices, for parochialism, and for xenophobia. There is ample evidence of this in such things as NIMBY attitudes, gated communities, and, more dramatically, the political fragmentation and ethnic cleansing that beset parts of Europe and Africa and that are sometimes justified by appeals to place identity.5

Bitter disputes over old places are a testament to how much these places matter. They matter. Sometimes they matter so much that their meaning may lead to war and to the destruction, as in times of conflict, of sites that symbolize a specific identity. A famous example is the destruction of Old Town Warsaw during World War II or, more recently, sites during the Bosnian War, in which “factions attacked the cultural heritage of other groups, acts that both violated the laws and customs of war and served to destroy these groups’ collective memory, both internally and to the outside world.”6

Nationalism and national identity have a dark history. One of the surprises of Rome for me is the prominent presence of buildings from the Fascist era. Mussolini made dramatic changes to the city plan and built hundreds of buildings, many of which consciously sought to tie the Fascist regime with the image of imperial Rome. The buildings are often monumental, stripped down versions of classical buildings – a distinctive style developed to create a new national identity, just as Americans built Greek and Roman style buildings to tie our nation to the republican and democratic ideals of the classical world. The Fascist identity Mussolini sought to create was utterly discredited with the defeat of the Axis in World War II. But the buildings remain and are actively used today. People differ about whether and how the meaning and history of these buildings should be acknowledged and recognized.

Reynold Reynolds, a filmmaker and a fellow during my tenure at the American Academy, shared with me a film he made about the demolition of the Palace of the Republic in Berlin, the former home of the People’s Assembly of East Germany. The palace was originally built in 1973 to 1974 on the site of the Berliner Schloss (which was heavily damaged by bombs in World War II and destroyed by the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in 1950), perhaps the most symbolically powerful site in Berlin. As a representation of the ideals of the GDR, the palace was without question a symbol of a national identity. But it was a national identity that was no longer valued when Germany was reunited in 1990. Despite the fact that the building represented a discredited regime, Reynolds’s project shows that many Berliners viewed the demolition as the erasure of their history and the loss of the opportunity for that history to be acknowledged and transformed. As Reynolds said, “thousands of citizens demonstrated against the planned demolition and hoped the building would be protected against historical censorship, but alas, one day twenty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the palace completely disappeared.”7

The continued presence of old places permits the acknowledgment of history – and former identities – and the transformation of identity over time – the necessary and continuous critical revision of identity informed by the past. Monticello now doesn’t hide the reality of Jefferson’s life with the enslaved people he owned, although that was not always the case. The enslaved people and their descendants – both literal and metaphorical – are now visible and present at the site. Monticello is the venue for understanding this history, which leads to a deeper understanding of our national identity.

I have heard people say that identity is different in America than in European countries, which have a more homogenous culture. As French historian Pierre Nora stated, “In the United States, for example, a country of plural memories and diverse traditions, historiography is more pragmatic. Different interpretations of the Revolution and the Civil War do not threaten the American tradition because, in some sense, no such thing exists.”8

Although I don’t necessarily agree with Nora’s statement, as I think about old places that represent an American national identity, it seems to me to be very American to voice critiques about that identity and to express diverse viewpoints about what the place means. Our old places of national identity can be the forum for this very American expression of views. What could be more patriotic than that?

When I was in Rome, I interviewed Jukka Jokilehto, who has been developing ideas about universal cultural value for the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property, about the fraught nature of identity. Jokilehto shared a critically important idea during our conversation. Places that reflect universal human values also reflect the diversity of cultural identities. In other words, places that are important to all of us arise from places that are important to some of us. When I spoke with Sofia Bosco, the Rome director of Fondo Ambiente Italiano (FAI), an Italian preservation organization, about old places in Italy, she clearly didn’t think about old places in Italy as only Italian. The FAI website features people all over the world talking about why places in Italy are important to them. As she told me: “Italy is a public museum of the history of everyone. . . . The physical identity of a country is more than a library or a warehouse. It’s there for you, for everyone.”

Old places embody our ever-changing shared identities and serve as tangible sites for transforming identity. Although we should guard against the dangers of nationalism, these old places, through the diversity of identities, reflect our universal humanity.

Notes

1. “FAQs: Battlefield Preservation,” Civil War Trust, accessed February 7, 2018, www.civilwar.org/about/faqs-battlefield-preservation.

2. The Historic Sites, Buildings, and Antiquities Act, codified at U.S. Code 16 (2018), section 461. The Historic Sites Act of 1935 expressly declared a national policy “to preserve for public use historic sites, buildings, and objects of national significant for the inspiration and benefit of the people of the United States.”

3. Edward W. Said, “Invention, Memory, and Place,” Critical Inquiry 26, no. 2 (2000): 177.

4. See, e.g., Diane Barthel, Historic Preservation Collective Memory and Historical Identity (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996); Max Page and Randall Mason, eds., Giving Preservation a History: Histories of Historic Preservation in the United States (New York: Routledge, 2004).

5. Edward C. Relph, “Reflections on Place and Placelessness,” Environment & Architectural Phenomenology Newsletter 7, no. 3 (Fall 1996), accessed February 23, 2018, www.arch.ksu.edu/seamon/Relph96.htm.

6. Shannon Supple, “Memory Slain: Recovering Cultural Heritage in Post-War Bosnia,” InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies 1, no. 2 (2005), https://cloudfront.escholarship.org/dist/prd/content/qt28c783b6/qt28c783b6.pdf?t=kro8fd&cv=lg.,2.

7. Gerhard Falkner and Reynold Reynolds, The Last Day of the Republic (Nurnberg: Starfruit Publicaitons, 2011), http://artstudioreynolds.com/artworks/city-films. See also Brian Ladd, The Ghosts of Berlin: Confronting German History in the Urban Landscape (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

8. Pierre Nora, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Memoire,” Representations 26 (1989): 10.To be continued

Return to Homepage • Return to Features Index

© 2019-2020 Short North Gazette, Columbus, Ohio. All rights reserved.

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com