Columbus, Ohio USA

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com

Jobs Now and Then

Industry in and around the Short North mostly memories

by Joel Knepp

joelknepp@outlook.com

November/December 2017 Issue

Return to Homepage • Return to Features Index

Return to Knepp Page

One of the biggest advantages of living in our beautiful Short North neighborhoods is easy access to employment. Most of us have to work, so why not make life more pleasant by living in close proximity to your workplace? For many of us city dwellers, the thought of facing twenty, forty, or even more minutes of rush-hour traffic every morning and evening, day after day, year after year sends cold chills down the spine. We prefer an energizing walk, bike ride, or a short drive or bus hop to get to the place where we labor to pay our bills, put food on the table, and buy the baby new shoes.

Plenty of jobs have existed in and around the Short North for a long time. Over the decades, the local job scene has in some ways stayed the same but in other ways has experienced monumental change. Columbus used to be big factory town; at one time we had 22 buggy-whip companies and many other large and small manufacturing enterprises. The area north of downtown that we now call the Short North was once a group of mixed neighborhoods where the wealthy and middle class lived close by many blue-collar industrial workers as well as many factories. Most of the scores of area factories that employed Short North residents and people from around Columbus and central Ohio are gone and rapidly fading from memory.

It’s likely that many current area residents aren’t even aware of our industrial past, which featured such local employers as Weinman Pump, Timken Roller Bearing, Jeffrey Manufacturing, Columbus Auto Parts, Lennox Furnace, Columbus Coated Fabrics, Ranco Controls, and many more. How many folks living in the Harrison Park townhouses and apartments around the junction of W. 1st Avenue and Perry Street realize that their luxury dwellings, party house, kiddie playground, gazebo, and swimming pool are built on top of and around what used to be Capital City Products, a vegetable-oil food products factory? Happily, they will never see the large pond of stinking green goo the factory left behind.Capital City Products

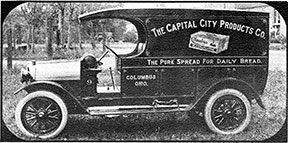

Capital City Products, a local presence for generations, was founded with eight employees in 1883 on Front Street by entrepreneurs Dennis Kelly and Henry Pirrung. Originally called the Capital City Dairy Company, they hit it big with an inexpensive butter substitute originating in France which they marketed as Butterine and we now call margarine. The business grew over the years and in 1901 moved to 13 acres of property at the junction of West 1st Avenue and Perry Street adjacent to the Olentangy River. Several other factories were located close by, including Central Ohio Oil Company, later called Sinclair Oil; Columbus Sucker Rod Company, a maker of long steel rods used in oil pumps; Columbus Coffin Company; and a sawmill. The area was served by a railroad spur, part of which is now a bike trail. Capital City Products developed mainly as a manufacturer of margarine and other edible consumer products such as mayonnaise, shortening, salad dressing, and cooking oil. These were marketed under names such as King Taste, Dainty Maid, BBS (Bakers Best Shortening), and Super Fry. Perhaps their best-known consumer product which continued at least into the 1970s was Dixie Margarine.

Gradually, the company evolved away from items marketed directly to consumers into a supplier of oil-derived products for the food industry and food-marketing organizations. For example, they made Kroger-brand shortening. They also made products used by bakers, candy makers, restaurants, and food industry giants such as Pillsbury, Keebler, and Campbell’s Soup. The company purchased large quantities of oils from around the world and built their own vegetable-oil refinery at the 1st Avenue site in 1921. In the 1970s the manufacturer maintained several oil storage and refining facilities in New Jersey and at its peak employed upwards of 600 workers. Mildred Todd, a long-time Short North resident, was one of those workers for thirty-two years. She describes the factory as having a family atmosphere, with good bosses and friendly, caring coworkers.

The Capital City Products Co., makers of Purity Butterine,

“The Pure Spread For Daily Bread.”Employees were members of the International Brotherhood of Firemen and Oilers Local 35. The union was well-funded and provided members with holiday turkeys as well as condolence gifts for workers experiencing family deaths. Management was generally supportive and almost paternal, and contract negotiations appear to have been mostly congenial, although at least one strike took place. In Mrs. Todd’s early years at the plant, management would provide her with a taxi ride home if she worked the late shift. The company provided and laundered uniforms; published an upbeat newsletter; sponsored basketball, softball golf, bowling, and tennis teams; and held an annual picnic.

Mrs. Todd enjoyed her varied jobs at the factory, and her earnings helped her and her husband own a comfortable home on Harrison Avenue and raise children. One of those children, Vanessa Todd, worked at the factory with her mom, eventually totaling 22 years before being laid off as the factory began its decline in 2000. Like her mom, she was able over the years to work in a wide variety of jobs through a bidding process based on union seniority and to buy a home and raise a family with her factory earnings. Vanessa’s father and Mildred’s husband George, a colorful local character, was a barber, race car driver, musician, and actor, but that’s another story.

As with many manufacturers, ownership and names of our local oil-products factory changed over the years. It’s a bit complicated, but roughly goes like this: In the late 1950s Stokely-Van Camp acquired the company, changing its name to Industrial Products Group. Later, Quaker Oats bought Stokely-Van Camp. Other names in more recent times were Karlshamns USA Inc. which became ABITEC, an acronym for Associated British Ingredient Technologies, which still maintains its corporate headquarters and research and development labs on West 1st Avenue near the old factory site. In later years the plant was called AC Humko. Even cheese behemoth Kraft was involved at the end. Kraft closed the factory in 2001 and centered its oil-products production in Cordova, Tennessee. Along with the loss of jobs, it must also be mentioned that our neighborhood was freed from nocturnal emissions of greasy air, and chunks of congealed coconut oil and other effluvia no longer entered the Olentangy River (and later the Scioto, Ohio, and Mississippi).Clark Grave Vault Company

The Clark Grave Vault Co. a family-owned business at 375 E. 5th Ave. has been manufacturing grave vaults since 1898 (see below). They’ve expanded into other products over the years. Massive machinery, a least one piece from the ‘30s, cut, stamp, shape, weld, wash, powder-coat/paint, and bake a variety of metal parts. At least one local factory from the old days is still in business. The Clark Grave Vault Company occupies a 14-acre chunk of land directly east of the railroad tracks between East 5th and East 2nd Avenues, with 300,000 square feet under the roof, a big operation by nearly anyone’s standards. The company has been in business since Hugh Clark invented the first air-seal, burglar-proof vault in 1898. These arch-topped metal containers were originally meant to prevent grave robbers from accessing the in-ground caskets of the newly deceased. Allen F. Beck purchased the company in 1919 and led it to become the first nationally advertised manufacturer and distributor of grave vaults. The company continued to grow and innovate through the 1930s, developing new and better types of product and offering grave vaults in a range of prices and metals. During World War II, it switched production to artillery shells, rockets, steel landing plates, tank hulls, airplane fuel tanks, and other war material. In the post-war era, Clark diversified by providing metal-stamping services to the automotive, appliance, and railroad industries.

In the 1990s, while other area factories were fading or gone, Clark began its own steel processing with the launch of CTL (Cut to Length) Steel, a separate division that marketed its services outside the company. Today Clark is still family-owned and is led by fourth-generation owner Mark Beck and his brother Doug. Mark guided me through a huge metal production building attached to the company offices and showrooms which holds a series of massive machines, metal parts, and finished products. The building is somewhat of a hodge-podge because during World War II when the factory was expanding, new building products were unavailable. Mr. Beck of that time period scoured the country for factory buildings closed during the Depression and had them disassembled, transported to Columbus, and reassembled. Clark workers would knock out a wall in the existing structure and attach each new addition, almost one per year during the peak expansion period.

The impressive factory machines, some new and at least one from the 1930s, cut, stamp, shape, weld, wash, powder-coat/paint, and bake a variety of metal parts, most of which end up as grave vaults. Mark explained that as burial choices have evolved, the business has adapted to accommodate burial of urns containing cremated remains. The plant now also manufactures urn vaults, a small vertical version of the grave vault. Both come in many different metals, finishes, and price levels. The 5th Avenue facility also produces and/or finishes metal parts for other companies and operates plants in West Virginia, Kentucky, and Kansas. Clark has also branched out into production of stone cemetery monuments at their out-of-state facilities. With the gradual introduction of computerization, robots, and conveyors, the current staff of about 60 is much reduced from levels of the past, especially during World War II when the plant employed 1,500 workers. The workers lost union representation in 1987 but are provided with a wide range of benefit choices, including health insurance and 401K plans. Many are long-time employees, including one worker who has been with Clark for 42 years. As older workers retire, the company continues to hire selectively as well as automate more of its manufacturing tasks. Most workers have been relieved of repetitive and potentially injurious tasks such as cutting and welding of metals. The plant places a high priority on worker safety and pollution control, exceeding many OSHA standards. Virtually all scrap from the various aspects of the manufacturing process is salvaged and reused in-house or sent out for recycling. The Beck family looks toward the future by continuing to seek out new opportunities to serve the funeral industry and other businesses in need of metal processing.

Rogue Fitness

Rogue Fitness, specializes in the marketing and manufacturing of equipment for CrossFit. They opened their new 600,000 sq ft facility a year ago at 1011 Cleveland Avenue in the Milo-Grogan neighborhood. Another notable exception to the gone and mostly forgotten manufacturers in the Columbus core is Rogue Fitness, a new player on the scene. The company originated in Toledo and now occupies a recently completed facility at the southwest corner of East 5th and Cleveland avenues. The long-abandoned site of the former Timken Roller Bearing Company factory was reborn as a modern business making and marketing gym and athletic equipment. Timken, based in Canton, closed its Columbus plant in 1989, citing aging facilities and prohibitively high production costs, at a loss of 219 jobs. Its recent replacement, Rogue, specializes in equipment for CrossFit, a strength and conditioning program consisting mainly of a mix of aerobic exercise, calisthenics, and weightlifting. The company is involved with many CrossFit competitive events held around the world, sponsors CrossFit athletes, and also distributes equipment in Europe.

Jeffrey Manufacturing Company

Jeffrey Manufacturing Company was founded at the end of the 19th Century by downtown banker Joseph A. Jeffrey. The plant was known as a progressive employer, both in terms of technological innovations and employee relations. Jeffrey experienced initial success with a coal-mining machine developed by Columbus inventor Francis Lechner. The machine and its descendants contributed substantially to a world-wide revolution in coal-mining efficiency. They work by rapidly undercutting veins of coal, replacing hours of uncomfortable pick-and-shovel work, hand drilling, and dangerous dynamite blasting. At first these chain-driven diggers were powered by compressed air, but Jeffery was quick to adopt the more effective electric motor after its development in 1888. From its location around North 4th Street and East 1st Avenue, the company manufactured a wide variety of coal-mining equipment over the years, including drive chains for the undercutting machines, locomotives, and coal crushers. At the company’s peak after World War I, Jeffrey occupied 36 acres on both sides of North 4th Street and employed 5,000 workers. During the Great Depression as coal mining slacked off, the company kept cash flowing with sales of road-building equipment built by the Galion Iron Works & Mfg. Co. in Galion, Ohio, acquired in 1929.

Among benefits for employees, in 1889 Jeffrey opened an on-site infirmary to deal with industrial accidents. Later it provided employees with a store, cafeteria, and a building & loan associating to help employees buy homes. The last president, Robert H. Jeffery, in an address given to the Columbus Historical Society in 2002, said of the company his great-grandfather founded: “I suppose this was paternalism, but it was paternalism at its best.”

Jeffery continued to experience success and growth in the 1930s and 40s but lost ground when it failed to switch its mining equipment from the rail-transportation method fast becoming obsolete. A Pittsburgh competitor founded by a former Jeffrey employee cut into their business by developing mining equipment that moved on treads or tires, eliminating the need to lay tracks in every mine tunnel. In the 60s, Jeffrey experienced a renewed level of success with the introduction of a machine called the Jeffrey Heliminer. These 50-ton monsters sold well because they could chew ten tons of coal per minute and were also effective in non-coal mining operations. But by this time, the bulk of the business, now called Jeffrey-Galion, was no longer in mining equipment manufacturing, but rather in the diverse products of three worldwide manufacturing groups that had been acquired over the years. In 1974 the Jeffery family decided to sell out to Dresser Industries, and the Jeffery Company became a manager of stocks and bonds purchased with the proceeds.

Dresser continued to operate the business into the ‘80s, and then the factory went through a series of ownership and name changes similar to those which occurred at Capital City Products a mile west on 1st Avenue. The manufacturing operation gradually declined. Finally, in a 1999 ceremony witnessed by the 36 remaining employees, the last piece of mining equipment left the much-shrunken factory. Now only a few buildings of what was once a huge complex still stand. The brick headquarters at the northeast corner of East 1st Avenue and North 4th Street has been repurposed as apartments. An adjacent former Jeffrey factory building now houses the State Library of Ohio, which holds a large collection of Jeffrey photographs and information. Housing developments are gradually filling in the remaining acres.

In the 21st Century, most area factory jobs have gone the way of the passenger pigeon as Columbus’s economy, like that of so many other American cities, has shifted away from manufacturing to services. Taking the place of most manufacturing jobs are thousands of positions at OSU, Battelle, and the many government, business, education, and health-related employers downtown and nearby, now providing a good living and an easy commute for many Short North residents.

Add to those the jobs with many small businesses that operate in and around the community, largely centered around High Street but increasingly on 4th and Summit Streets and in nearby Grandview Heights and Upper Arlington. The building boom all around downtown, OSU, and the Short North continues to snowball, providing much work for those in the construction industry, albeit irritating folks who are trying to go anywhere with their many roadblocks and bottlenecks. In short, the employment future for Short North residents looks rosy, which is a good thing because rents, home prices, property taxes, as well as medical and educational costs, not to mention cocktail prices, are going nowhere but up.

Joel Knepp is a freelance writer living in Victorian Village.

© 2017 Short North Gazette, Columbus, Ohio. All rights reserved.

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com