Columbus, Ohio USA

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com

Encountering W.C. Hemming

The artist, the man

By Karen Edwards

April 2017 Issue

Return to Homepage • Return to Features Index

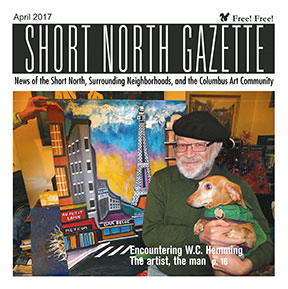

W.C. Hemming and Soon Ja Hemming with Magic Night. Photo by Gus Brunsman III You look at him, a spry 70-year old with flyaway hair and a face full of whiskers and you think to yourself: “Don’t I know him? He looks familiar. Haven’t I seen him before?” And the fact is, maybe you have.

After all, W.C. Hemming has been around. Maybe you’ve seen him in the Short North Tavern. He’s shown up there for years. Or maybe you’ve spotted him at the Doo Dah parade, cheering on the Marching Fidels. He’s in the crowd there somewhere. If it’s St. Patrick’s Day, you may find him at O’Reilly’s Pub, hoisting a pint with all those other brothers and sisters of the Auld Sod, even if the Auld Sod happens to be in Clintonville. Of course, there’s a chance you may have run into him on Paris’s Left Bank. Paris is far and away his favorite city. Or maybe it’s just that when he slaps a black beret over that unruly mass of white hair, he looks the quintessential image of an artist. All he needs is a smock.

But even if you haven’t run across Hemming himself, chances are you’ve encountered his art. Hemming is a prolific artist who paints like he’s been personally charged with single-handedly filling every art gallery in town.

“He paints with such a passion,” says his wife Soon Ja.The Hemming style

That passion shows up in his art, much of which sits about his living room like the unframed dreams of a visionary. There’s an Eiffel Tower, of course, and a Paris street scene; a likeness of Humphrey Bogart and Edgar Allan Poe; there’s a flying saucer spreading a cone of light over a cow. “The title of that one is ‘They only stopped for hamburgers,’” says Hemming with a chortle.

If you get that gleeful sense of humor with just a touch of gallows in it, you get W.C. Hemming. His art, his life, have been a mix of both.

Hemming grew up in Columbus, in a home with his brother Patrick, his sister, Brenda, their father, a mechanic and their mother who occasionally fashioned jewelry. “Other than that, there was no art in the home or any artists,” he says.

Still, his mother encouraged him to check out art books from the library when they visited – maybe to balance against all those paperback novels Hemming would pick up for a dime at the local Goodwill. “We were poor, but I liked to read,” he says.

By the time he reached high school, however, Hemming had fallen in love with art. “At that point,” he says, “I was just drawing cartoons and things like Davy Crockett in a coonskin cap.” Still, one of his cartoons found its way into The Sundial, a now defunct student publication of the Ohio State University. That clip proved to be enough to earn him admission into the prestigious Columbus College of Art and Design. Hemming will be the first to admit it wasn’t much of a portfolio – those cartoons and coonskin caps. “I showed my drawings to Joseph Canzani who was the president at that time,” he says. “He told me, ‘Okay. We’ll take a chance on you.’”The three goals

Hemming was thrilled. “I had three goals at that time. The first one was to be an artist, and that meant I had to go to an art school,” he says.

So first goal accomplished. Hemming’s time at CCAD was a period of exploration in art and all of its forms. He found that he gravitated to acrylics which allowed him to paint faster and less permanently than in oil. They also allowed him to mix colors in a way that oils never would.

Even now, when he paints, Hemming turns to acrylics. “I specialize in them,” he says. And over the years, he has developed a palette of bold, vivid color that identifies all of his work. They’ve become a signature of his style. “I don’t paint in pastels,” he says simply.

Hemming would have quite happily continued with his art following his time at CCAD – except for two things. For all of his artistic inclination, Hemming was born and raised a pragmatist. He knew in order to eat, he needed steady income, not the kind of feast-and-famine cycles that identify the lifestyle of most artists. That meant a job. At the same time, the Vietnam War was in full force, snapping up young men in a draft that brooked no excuses. Hemming was drafted. That took care, at least, of the steady income, but men – young boys, really – were dying overseas, in the heart and heat of the Vietnamese jungles. It was not the kind of steady income Hemming was dreaming about.

But luck seemed to be on his side. “They asked for volunteers to serve as draftsmen,” Hemming recounts. He had enough art experience to think that he could possibly make a go of it, though he didn’t know the first thing about drafting, well, anything. Hemming’s hand went up. It was the only one. But as he was about to learn, draftsmen in the U.S. Army stayed Stateside. Hemming never saw the kind of overseas action that brought so many Vietnam vets home with severe cases of post-traumatic stress disorder. Putting up his hand when he did, volunteering when no one else would – “It was the smartest move I every made,” he says now.

After his army discharge, Hemming pursued a history degree at OSU. When he graduated, “I learned that a history degree is good for a job in social work,” he says.

Hemming worked with mentally disabled individuals for 11 years before deciding that was enough time for that pursuit. He returned to OSU, this time for a job. He worked, first as a room scheduler, a high-stress job that proved to be an art in and of itself. “I was working with prima donnas who were all jockeying to be in the same room at the same time,” he says now with a laugh. That job lasted 10 years before he finally landed in the psychology department as appointments secretary and building coordinator.

Resident artist

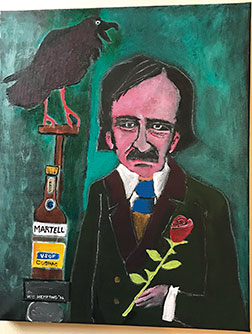

Edgar Allan Poe, by W.C. Hemming During his various careers, however, Hemming continued to paint. Although he compares himself to expressionists like Jack Levine and Moses Seymour – Hemming may be more adroitly compared to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who used to prowl the seedy underbelly of Paris, stopping by bars, dance halls and clubs to sketch its patrons, owners and staff. “I used to draw a lot of caricatures,” says Hemming. His modus operandi, like Lautrec, was to plant himself at one of the bars in the OSU area and draw quick character sketches of those who worked there and those who came in. He was the resident artist for years at Dick’s Den.

But then, something happened. Hemming met, fell in love with and married Soon Ja. Credit her for the landscapes Hemming now prefers to paint.

“I would look at his paintings, and I’d never see any landscapes,” she says. “I like landscapes, so I asked him why he never painted any.”

“I was petrified of landscapes,” Hemming admits. “They seemed so static. I wasn’t sure how to enliven them.”

Yet despite his reservations, Hemming began to paint landscapes. Or at least consider painting them. See, Hemming may paint with passion, and there’s no question when looking at his art that he is passionate about what he paints, but he is also an organized painter. “His mind is set up so that he paints from an organized list,” says Soon Ja.The Hemming method

A list?

“Once a year, I brainstorm a list of topics I might like to paint,” he says. He begins with random images he comes across, usually from a wide variety of national and international websites. He downloads the images he likes the best and researches them. If it’s an image of a place, he’ll research the place. If it’s an image like the spaceship, the unidentified flying object that sits over a field, he’ll simply let loose his imagination. “I thought maybe the spaceship might pick up a cow in that field,” he says. The images he keeps are stacked in piles. From those, he compiles a list of portraits, caricatures, landscapes and other works he wants to create. “I’ll look at what we need to do for a show,” he says, in addition to his own whims. Then, he begins to paint.

“The pictures I collect are a starting point,” he says. They are only ideas. He sketches outlines on a blank canvas, putting in some basic colors, using a light brushstroke, then he’ll set to work on the actual painting process, adding more and more color, layers of color, “sometimes as many as 20,” says Hemming. Then he works in the details. In all those scenes he paints, take time to look more closely at those details. You may find him in a few of them, a self-portrait of sorts. “I do sometimes put myself in a painting,” he says.

As far as the intentions behind his art, Hemming says he tries to convey an atmosphere in his work. “When someone looks at my art, I want them to feel the same mood and expression I felt when I looked at that picture.” It’s an innate, unconscious talent, really. He holds up a painting. A bolt of lightning splits a dark sky over a seaside castle. The sea is churly, choppy. “I looked at a picture of a lightning bolt I had collected, and I wanted to convey that sense of power,” he says. Now look again at Hemming’s painting. The bolt, high in the sky, is bolder, brighter than anything on the page. Look at the castle. Not a home or a pretty little cottage – it’s a strong, fortified, stone castle. Look at the sea. Not serene and peaceful, lapping the shore, but angry, foaming, cresting water. It’s all power, all the way through the picture. But it’s not a studied decision to include those images. They flow from him naturally, into the painting.The second goal

Hemming had three goals as a young art student, remember? The second goal was to be shown internationally.

Yes, he’s visited Paris four times. “In ’78, ’82, ’84 and in 2013,” he rattles off like the answer to one of his history tests. But he achieved his second goal, his international showing, by sitting right at home in Clintonville.

After all, the Internet, by the early 2000s had become a major force in our lives – and in the art world as well. In 2003, Hemming learned of a computer art fair that Barcelona, Spain, held annually. “I sent off some of my work, and to my surprise, I was accepted into the show.” His work was displayed in the city’s Gothic Quarter, the heart of old Barcelona.

So, goal number two accomplished. But that’s not all. “I even sold one of my pieces,” as a result of the Barcelona exhibit, says Hemming. That picture depicted the old Prague Castle, painted with a pink sky. That means, of course, that Hemming has not only been part of an international exhibition, but that his work also hangs in the home of one discerning European. And as if that wasn’t enough, that exhibition also landed Hemming and his art in an Italian art encyclopedia, a heavy tome, that Hemming will proudly hand you to verify the fact. His painting Portrait of George Fambro – a 36” x 28” acrylic and oil on canvas – is featured, indeed, in the Dizionario Enciclopedico Internazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea 2002/2003.Domestic success

It may seem small, by comparison, to mention that Hemming has also had plenty of exhibits in this country. Again, you can credit Soon Ja, who believes enough in her husband’s art, that she makes the rounds to various galleries and exhibit space to show off examples of Hemming’s work.

“The first big show I had was at the Cultural Art Center in 1985,” says Hemming. Since then, his work has appeared in exhibits at the Short North Tavern, Columbus State University, at city hall, various Short North galleries, and galleries in Ann Arbor, Michigan, as well.

And let’s not forget the Doo Dah posters he’s turned out – year after year of art featuring the Marching Fidels, that iconic group of Fidel Castro look-alikes who are the parade’s heart and soul and arguably its most-recognizable feature. The posters were wildly popular, as was the original artwork. He’d probably still be selling his Doo Dah pictures if he hadn’t grown a little bored with it all. He says he relieved his boredom for a time by painting the Marching Fidels a little more realistically. “I’d go to the parade, and I saw they were getting a little older, a little grayer, so the next year, I’d paint them that way,” he says. One of his last posters for the parade was his own tongue-in-cheek salute to the longevity of the Doo-Dah and his own relationship with it. “I painted the Marching Fidels walking down High Street on canes and walkers,” he says with a smile. Remember that gleeful, gallows humor? Well, there it was – in one painting – on full display.That last goal

But while humor often shows up in his art, art is still something this septuagenarian takes seriously. “My work has definitely evolved,” Hemming says, as he surveys his living room landscape filled with his art. “I see maturity in my work now. I’ve refined my skills. I’ve grown as an artist. I experiment more now.” After painting more than 450 works of art, he’s bound to have moved on from cartoons and coonskin caps.

If he had it to do over again, though, Hemming says he wouldn’t change a thing.

Well, maybe one thing. “I’d probably be living somewhere else, not in Columbus,” he says. Where that might be is anyone’s guess. But you wouldn’t be wrong if you guessed Paris. He’d still be an artist, of course, painting from his list. “So I never get burned out of ideas,” he says. But as far as a legacy is concerned, Hemming’s pragmatism comes roaring back. “I hope people say I was original,” And he wants people to realize he achieved his version of success, “my way.”

Hemming’s third goal as a young art student is still out there. “I want my art to be in a museum one day,” he says.

If his other two goals are any indication, he might well be. After all, he’s still painting. He’s still exhibiting. (Catch his latest show this month at the Short North Tavern – “The two types of subject matter he paints, landscapes and mystical-looking pieces, appeal to the melting pot of people at the Short North Tavern,” says Tavern curator Colleen Sexton.) In other words, don’t count him out, even at the ripe old age of 70.

So, should you happen to encounter W.C. Hemming, you’ll be forgiven if you take a second look. “Don’t I know you? You look familiar,” you’ll say. “Maybe,” he’ll respond. Then, with the satisfied grin of a guy who has met nearly all of his life-long goals, he’ll likely tell you: “I’m the guy whose work hangs in a museum, whose work has been shown nationally and internationally, whose work appears in a European encyclopedia.”

“I’m an artist.”An exhibit of William C. Hemming’s artwork is showing at the Short North Tavern, 674 N. High St., throughout April 2017. To view other works, visit Facebook at William C. Hemming or email morbius1946@gmail.com for more information.

See Also: W. C. Hemming: Creating a Legacy, by Jeff Bell January 2001 A website with his art is at https://morbius1946.wixsite.com/wchemming

© 2017-2020 Short North Gazette, Columbus, Ohio. All rights reserved.

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com