Columbus, Ohio USA

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com

Pop Renaissance

Contributing columnist for monthly newspaper Short North Gazette

Jared Gardner teaches American literature, film and popular culture at the Ohio State University

Jared Gardner

editor@guttergeek.com

THIS IS AN ARCHIVE

This page contains articles from 2010 - follow links at left for 2009, 2011Writer's Web site www.jaredgardner.org

Visit Archive: Pop Renaissance 2009

Visit Current: Pop Renaissance 2011

Return to HomepageHarvey Pekar, 1939-2010

SEPTEMBER 2010 (reprint from www.tcj.com/guttergeek)

Monday, July 12, 2010

I haven’t even begun to absorb the news that Harvey Pekar died today, although I have been staring at the headline at the Cleveland Plain Dealer for the better part of two hours. For those of us who have been following his life for over thirty years, the loss will be a deep one: the loss of friend, whether we ever met the man or not, whose life we have come to know as intimately as can be imagined and whom we have grown to love despite, and because of, the fault-lines he so painfully and lovingly explored.

I only had the pleasure to meet Harvey once, when a few years ago he visited Columbus for a talk, and I was given the terrifying job of talking with him in front of a packed auditorium. Despite many warnings in the weeks leading up to the event as to the public humiliation I had signed up for, I found Harvey – both on stage and off – generous, smart, thoughtful, and warm. And in truth, there is little to be surprised at for anyone who has spent time with his stories (as opposed to YouTube videos of his appearances on David Letterman).

I first encountered American Splendor as a teenager sometime around 1979 in a Greenwich Village comics shop where I had gone for my weekly fix of whatever crap I was reading at the time. It had been a bad year on the whole: Howard the Duck and Tomb of Dracula had both been canceled. The only bright light on the horizon was this kid Frank Miller who had taken over Daredevil. For the most part, everything good in comics seemed to have happened in the past before I was old enough to appreciate it: E.C., early ‘60s Marvel, and most titillating of all to my 13-year old imagination, the underground comix revolution that had petered out earlier in the decade. I had just said something to this effect to my companion when the owner, who had never said a word to me in my several years of frequenting his establishment, suggested I might be ready for the more “mature” comics he had in the back of the store.

To be clear, I was not ready. There they were, these comics that didn’t look at all like comics, with titles like Tits & Clits, Anarchy, Dope Comix, and Bizarre Sex. But I could not walk away without picking something up or I would never be able to show my face again, and so I grabbed the safest looking one I could find: American Splendor #4. The cover seemed innocuous enough to avoid censorial glares on the subway home – two guys trading records, each thinking to themselves that they had played the other for a sucker – but inside was sure to be some wild, sexy, offensive stuff. After all, while the cover tamely promised only “Stories about Record Collecting and Working,” the notorious Robert Crumb was one of the contributors, which to any knowing teenager meant dirty stuff was surely waiting inside.

Needless to say, it was not. The book really did just contain stories about record collecting and working, neither activities in which I took much interest; but with no Howard the Duck and without the guts to buy Bizarre Sex I was stuck with little other reading material for the ride back to Brooklyn. And after reading those sixty pages of stories – about how Pekar first met Crumb, how he starting making comics, how he loses his temper in the office while trying to get through yet another day as a file clerk, about his memories of working in his father’s grocery store, about his co-worker who slowly goes mad after the death of her husband – I was hooked. At age thirteen I had for the first time been given a window into an adult world that was neither glamorous nor melodramatic but seemed honest, true, precisely what teachers or parents could not bring themselves to admit to a child about to enter the adult world. The adult life that awaited me would neither be romantic or tragic: it would instead be a series of small, repetetive movements out of which any beauty, any poetry, would be only what I found a way to wring from it.

From that day, my interest in superhero comics dropped off measurably and soon my interest in comics in general followed suit, given how little at the time promised similar insights, similar truths. But I stayed with Harvey for the next three decades. I made sense of my parents’ divorce through Harvey’s accounts of his own – also the disappointment of teenage sex, the mind-numbing pain of the first real job, the endless stupidity of other people, and the strange, unlikely epiphanies that happen on overpasses and in grocery stores. All of those shocks and jolts of everyday life were made less jarring from having lived them first vicariously through Harvey.

When I came fully back to comics in the early 1990s, there was more on the shelves that took the kinds of chances on the quotidian as American Splendor had since 1976. And of course in the years to follow, we have seen the quotidian come to rival the superheroic and the supernatural as the most familiar subject for comics creators. To say all of this is due to Harvey would be of course precisely the kind of overstatement he would have scoffed at, and yet it is true that without Harvey, it is almost entirely impossible to imagine an entire generation of comics.

In my own case, it is impossible not to see my life and the choices I have made as owing more than a little to the honesty and wisdom of Harvey Pekar’s autobiographical comics. As I prepare to confront whatever comes next, I know I will be returning to his comics with the same sense of wonder and gratitude that I experienced more than thirty years ago. But man, I’m gonna miss him. © www.tcj.com/guttergeekLost in Translation: Everything I Can't Tell You About How It Ended and Why

JUNE 2010

I briefly contemplated leaving the interweb for good the other day. After six tumultuous seasons, the most remarkable drama ever to appear on network television came to an end, and before our collective eyes were even dry the messages started flooding in. On Facebook, on Twitter, on email, on text: “What did you guys think?” “Can you believe how horrible it was?” “I want my six years back!” Or, somehow worst of all, “I think the ending proved how only Love really matters.”

I quickly shut my laptop and headed up to bed, my mind spinning from what I had just watched and by my own surprisingly emotional response to it all. The last thing I wanted to do was to try and transcribe my thoughts in text-message-speak: “IDK. IMHO 2 soon. L8r?”

But the next morning, it was worse. The pontificators had begun their ritual deflations and dissections, and my inbox quickly filled up with links and quotes designed to provoke me into a response.

Did I, like them, feel cheated now that the show was over, so many questions unanswered, so many loose ends still flapping in the stiff Hawaiian breeze? Those who had resisted my urgings for six years to watch the show were the worst of all. Many of them had turned in for the finale (it was an “event,” after all) or just waited for the post-game analysis, and then declared their deep self-satisfaction that they had not allowed themselves to be manipulated into investing the considerable time and energy the show demanded.

And in truth, these folks had no idea how much time and energy the show cajoled its devoted fans to invest. By its very nature, Lost encouraged multiple viewings, and most serious Lost-ies I knew had watched all six seasons numerous times. Part of the pleasure of the show, after all, was finding new details, new insights each time through. Lost was the perfect network show for the digital age, not only getting us all to watch it as it premiered each season but also to preorder the DVDs so we could spend the off-season going through the episodes again in search of clues we inevitably missed the first time around. And then to the Internet, to the wikis, chat rooms, interviews, and fansites, where each episode was dissected with the obsessive care of conspiracy theorists working over the Zapruder. The truth, we knew, was out there, as Agent Mulder promised in one of the long-arc dramas that paved the way for the new golden age of television that Lost ultimately crowned.

“What truth?” will ask my pious friends (the kind who insist on calling their TV set a “monitor” because they use it only to screen Buñuel films and never to watch network programming). “It all added up to nothing, just a series of red herrings and big media manipulation leading to a Hallmark message straight out of Touched by an Angel.” Resisting the urge to ask them how they managed to watch Touched by an Angel on their “monitor,” I would, if I deigned to respond at all, explain to them that the point was never – at least for me, and I think I speak for countless others – about making it all add up, about finding the final answer, about arriving at some rational explanation for what the Island was or did. But I would be wasting my breath, just as they will remain convinced no matter what I say that I had been profoundly wasting my time.

In truth, I have had no interest in engaging these conversations, not because I shy from pointless debates. Heck, that’s pretty much what I do for a living. Instead, I have been retreating into an uncharacteristic silence because I needed time to process my response to the show’s conclusion. And for the first time in six years, I wanted to process alone. I have not visited a single Lost website since it ended. At first I thought it was because I did not want to know if my fellow fans too felt betrayed or disappointed by the conclusion. But as the week went on I realized it was because now that the show was over, where it went from here was no longer a collaborative enterprise. It was mine, for better or worse, to do with as I chose.

That was, in fact, the gift the show left its fans in the final episode – and I understand that it well might not be a gift that everyone will appreciate. In the place of tidy answers or a filling-in of all the gaps in the show’s increasingly Byzantine mythology, the finale left us with perhaps the biggest gaps of all. As Jack comes to the realization in the show’s final moments that he is in fact dead, his father, Christian, tells him, “Everyone dies sometime, kiddo. Some of them before you; some long after you.” We know, of course, who has died before Jack: Locke, Boone, Juliette, Sun and Jin, Said and that blonde lady Said unaccountably ends up with instead of his true love, Nadia, in the great purgatorial waiting room the sideways world of season six turned out to be. And we know, now, who died after Jack: everyone else – including (no doubt long, long after) the new caretakers of the Island, Hurley and Ben, now gifted with the agelessness that comes with the job.

What we don’t know, of course, is how they died, but I no longer care. They died because, as Christian reminds us (and yes, we do need reminding, so eager are we to forget this most basic and indigestible of facts), “everyone dies sometime.” I was no longer thinking about death, however, but wondering over life: What did they do? How did they live? What happened to Sawyer, Kate, and Claire when they returned to Los Angeles? How did Hurley and Ben govern the island differently than their predecessors, Jacob and Richard? And what of Richard, who lived more than a century in servitude to the Island and to Jacob’s god-games: How did this nineteenth-century man adjust to 21st-century civilization upon his return?

The show ended because, well, every show ends sometime, kiddo. Sure, the creators of the show could have tied everything up in a neat and tidy package and left us to accept it or reject it. Instead, they left us what amounts to a do-it-yourself starter package to keep the story going on our own, which is – for me, at least – the most thoughtful gift they could have given their devoted fans whose collaborative investments in the show’s mythologies are at least as responsible for its impact as the work of the screenwriters or the actors. As Lost comes to its close in the implausibly ecumenical church in which our characters have been gathering to embrace each other and their own dead selves, Christian opens the door on the gift we are being left with: a white screen, a blank page. The rest is up to us.

So to all those who claim to have loved Lost but been betrayed or in some way cheated by the finale, I can say only “get to work.” Whether you like how it ends has everything to do with the choices you make as you imaginatively fill in the gaps of all the stories left untold. And if doing that kind of work seems to you pointless or an unreasonable demand for a television show to make on your time or imaginative energies, then I suspect you never really liked the show much at all – or somehow fooled yourself into liking it for the wrong reasons. Nothing wrong with that, as long as you had a good time until your final “betrayal.” But for the rest of us, please, keep it to yourself: we’re busy playing with our gift.To Be Continued: The Birth of the Open-Ended Serial (and the Future of Film?)

MARCH 2010

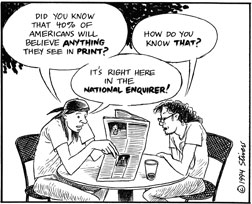

© Mark Stivers It is an underappreciated fact that in the early decades of the last century an entirely new mode of storytelling came into existence. I don’t mean a new medium, although there certainly were plenty of new technologies for telling stories in those head-spinning days – film being the one most likely to come to mind today. But actually film did not participate in this particular innovation. No, what I am describing here is the new narrative mode of the open-ended serial – a form we today most familiarly associate with the soap opera or an ongoing television series like Dr. Who, whose adventures have by this time crossed many decades and several different media (including television, radio, comics). But in the early years of the twentieth century, the mediums that brought to life the new open-ended serial were the newspaper comic strip and, a decade or so later, radio. Today of course serial radio dramas are a thing of the past (it is fascinating to play some of the radio serials from the ‘30s for young people today and watch their obvious discomfort as they try and figure out what it is they should be looking at while they listen). And the newspaper comic strip is itself on the verge of extinction, along with its host, the newspaper itself. But just a little shy of a century ago, the comic strip was popular in ways we can hardly imagine today.

Not just popular, but important – even headline news. One example serves in many ways to describe the phenomenon better than any I can think of: Sidney Smith’s The Gumps. Largely forgotten today, Smith’s strip was arguably the most influential strip of the 1920s. Readers followed the story compulsively, and they wrote in regularly with demands, pleas and suggestions for future installments. And Smith encouraged them to do so, inviting his readers to share their opinions on his ordinary American family and their adventures, holding contests for the best solution to the various problems they faced, and even copying letters into his strip itself.

Smith loved to get his readers debating about his characters, and one of his most popular storylines was the 1922 question as to whether the Gumps’ kind and extremely wealthy Uncle Bim should be allowed to marry the Widow Zander, who many readers felt was just after Bim’s money. Of course many readers also felt that our protagonists, Andy and Min Gump, objected to Mrs. Zander only because they wanted to keep Bim’s fortune for themselves. Smith made sure both sides had plenty of ammunition for their respective side and then set them loose, inviting his readers to help him decide Bim’s romantic fate.

Finally, on the day of the wedding, Smith had his readers in such a state of agitation that the strip had become, literally, front page news. On April 13, the Columbus Enquirer-Sun, while Mrs. Zander waited impatiently for her missing bridegroom, asked, “What Has Become of Uncle Bim?” The next day trade was suspended at the Minneapolis board of trade while newsboys hawked their wares announcing the big news: “Uncle Bim—no marriage!” As the Tribune’s cartoon syndicate head Arthur Crawford described the phenomenon:“Rotary clubs passed resolutions and sent telegrams; newspapers carried eight-column heads on the news of the day’s strip; newspapers shouted the latest developments and millions of families fought to be first at the paper.”

One would think Smith would not top the excitement generated around his 1922 marriage plot, but in 1929 he came up with the storyline that generated more interest still. While her fiancé was rotting in jail for a crime he did not commit, Mary Gold, a beloved character in the strip, was slowly wasting away in her sickbed. None of Smith’s millions of readers truly believed he would allow Mary to die, but they wrote in by the thousands to plead for her speedy recovery and her reunion with her fiancé, Tom Carr. On February 28 of that year, Mississippi Governor Bilbo went so far as to grant the fictional Carr a full and official pardon, which he promptly sent on to Sidney Smith. But all of it turned out to be in vain, as Mary Gold died just before the pardoned Tom could make it to her side, becoming the first recurring comic strip character to die.

Today the death of comic characters is a regular event, but in superhero comic books, such deaths inevitably spark the sideline debates as to how long it would be before the hero was inevitably, magically brought back to life. But Mary Gold, Smith quickly made it very clear, was well and truly dead. Immediately, the newspapers across the country carrying the strip were deluged with calls and letters – not only of protest, but of grief, with readers askingwhere to send the flowers or when the funeral service would be held. As one local paper reported: “Some sympathizing reader of the Herald’s comic page has sent a bouquet of pink and white paper sweet peas with a card attached, ‘For Mary Gold’s funeral.’ The flowers will be forwarded to Sid Smith, Mary Gold’s creator, with the grief of the unknown sender.” “Mary Gold died Monday night,” a Tennessee paper reported. “She was a creation of the imagination. … Yet, strangely enough, she seemed more real to hundreds of thousands of readers of ‘The Gumps’ than those persons whom they were wont to meet in the every day walks of life.” Suddenly the fun of playing along with Smith’s interactive dramas – legislatures passing resolutions on behalf of a particular character, governors pardoning a fictional criminal – seemed not quite so fun, and the papers paused to wonder whether Smith in fact had the “right” to do this to them. A week after her death, papers continued to report demands from readers that they “Please find some way to have her come alive.”

There is much that is remarkable about all of this, but much that is of course familiar. We have seen the open-ended serial form that The Gumps and other comic strips first developed in the 1920s expand to other media over the past several decades: radio, television, the comic book, and now the Internet. The grief at the death of a character in a beloved soap will never reach the kind of fever pitch that the nation experienced in 1929 because we have so many serials (and so many media) competing for our attention and our time – and serial narrative by its nature requires a significant investment of time and attention. But we can think of countless examples in recent years that mirror the collective feeling and sense of collective ownership that the open-ended serial encourages – whether it is the fans literally taking over the continuation of Dr. Who after BBC canceled it for several years, the phenomenon of fan fiction dedicated to creating new adventures or even bringing back to life characters lost or series canceled, or the interactive fan sites devoted to parsing out every detail of the choices creators make for various television series and offering advice to the producers (advice which increasingly the producers find it in their interest to take very seriously indeed).

In fact, the one 20th-century media form that has not found a way to embrace the open-ended serial has been film. Yes, there are serial films dating back the “serial queen” adventures of the teens and twenties (Perils of Pauline) and the intergalactic cliffhangers of the ‘30s and ‘40s (Flash Gordon). But these were never open-ended: they were advertised from the start as being essentially longer stories divided up into installments, each with its own requisite cliff-hanger to bring the audience back to the theater the following week. The death of Mary Gold, on the other hand, did not bring an end to The Gumps: their story continued the next day and on into the future, ultimately derailed only by the real-life death of Sidney Smith in a car accident in 1935, from which the strip never fully recovered.

Movies, it would seem, are not formally suited to the open-ended serial. But in the early years of the 21st century we are seeing signs that it might well be heading in that direction at long last. We see it most clearly in ongoing “franchise” films like the X-Men or Batman series, which maintain the fantasy that the story will extend into the future in perpetuity in film after film. But we see it as well in the increasing turn to the sequel: this year will see the third film in the Meet the Parents series, the seventh film in the Saw series, and perhaps even more shockingly, the second film in the Hairspray saga (who knew?). There is nothing new in sequels, of course; they are generally safe investments for an industry increasingly adverse (I was going to say “creatively bankrupt”) to anything new and untried. But I do believe the explosion of sequels, largely inspired by the success of what are essentially open-ended serial film franchises from the world of superhero comics, might in the end be Hollywood’s creative salvation, as unlikely as this year’s crop might appear. As we saw with the phenomenon of The Gumps, audiences like their media best when it becomes an “event” in which “entertainment” blurs into “news”; we like our stories collaborative and interactive; and our series open-ended, ongoing, and never-ending.

To be continued…

Best ofMy Favorites of 2009FEBRUARY 2010

One of the great pleasures of the year’s end is the opportunity to look back and review the state of the Pop Renaissance in all of its various departments. I don’t pretend, however, to have exhausted even a fraction of the riches of 2009 in any field except for comics, where I make my second home (in fact, do visit me at my new second home at http://tcj.com/guttergeek). So I won’t be so vain as to suggest that my favorites are in fact “the best” of the year.

Nor do I want to. Part of the fun of popular culture at our present moment is the liberation from the fantasy that one could possibly read, see, and listen to everything worth reading, seeing, and listening to. This is a period of cacophony and surplus in our popular culture choices. No doubt there will be a backlash against all this choice on the part of audiences and producers alike in years to come. But I intend to luxuriate in this particular excess as long as I can. After all, in a period of economic constraint, why shouldn’t we have all the cultural bon bons we can eat? And yet, as my choices below make clear, there is also something to be said for bringing some austerity measures even to our popular culture.TV

For me, this was the easy one, although I confess to being surprised by my answer. In 2008, my favorite show by a healthy margin was Mad Men, then in its second season and promising in every way to be the heir to The Sopranos I was desperately hoping for. But season three in 2009 was a very sizable disappointment for me, one that often made me doubt my earlier attachments to the show. I am desperately hoping that Lost’s final season will be my favorite show of 2010, but all in all few continuing shows (aside from the always brilliant 30 Rock) really shone in 2009.

And most of the new shows fell pretty flat as well. I was still holding out hope for Joss Whedon’s Doll House, but Fox apparently did not share my optimism (they announced the cancellation of the show on November 11). Southland seemed especially promising, but apparently not to NBC, which canceled the show a month earlier. V, which premiered this fall, is good remake fun, but in the end it is just a reminder of how much better was the original (whether you are referring to the ‘80s mini-series or the even closer source of the much-missed Battlestar Gallactica). No, if anything, this year in TV was a reminder that “the new golden age of television,” abruptly short-circuited by the writer’s strike of 2007, is well and truly over.

But diminished expectations have their own rewards, and thus it was that the best show of the year snuck up on me from where I would have least expected to look for it: in the form of a musical comedy set in a high school in Lima, Ohio. Glee started off weak, it must be said, as if desperately trying to hit all the script notes from far too many conference calls with far too many interfering producers. But in the end, despite some flaws in the casting and an Auto-Tune set way too high, this show won me over completely for being somehow combining more guilty pleasures into a perverse yet decidedly guiltless stew than I ever imagined possible. Good things happen at the end of “golden ages,” too; they just tend to be a whole lot smaller and stranger.Movies

Actually, this was easy, too. Hollywood is now so far removed from its last period of meaningful creativity (arguably, a mini-“golden age” of sorts happened in the early days of Sundance and the Indie revolution) that there are never more than a handful of candidates for films I can even sit through without falling asleep or getting drunk. This year was one of the worst I can recall, and most of the films I did admire were either B-movie masterpieces (Zombieland, Inglorious Basterds, The Hangover) or so depressing I’m not sure I can recommend them to anyone (Precious). Only one film for me was the kind that makes me want to sit people down and make them watch it.

District 9 is itself a B-movie masterpiece of a kind, made from a surprisingly small budget with a cast of largely unknown or first-time actors in South Africa. And it is, in many ways, as depressing as Precious, even if the misery and cruelty it describes is told through the allegorical filter of science fiction. Using a refugee camp of displaced aliens interned in South Africa to stand for countless very real situations of dehumanization in counties around the world (including right here at home), District 9 is a science fiction adventure that offers one of the most biting and believable critiques of the fundamental inhumanity of dividing people – whether by race, by country (or planet) of origin, or by religion. And somehow, magically, as only film can do, it is also brilliant good fun.Music

If TV and Hollywood were relatively easy picks for me because the pool was so very shallow, the field of pop music is overflowing with possibilities this year. There is something ironic about the fact that even as we hear dire predictions of the death of the music industry (predictions that seemed tragically epitomized by the very real death of the industry’s last true Pop Idol, Michael Jackson, this year) we see a greater range of exciting music than I remember finding in more than a decade. Actually, I was being ironic when I said there was something “ironic” about this fact: it makes perfect sense for reasons I will talk more about in the coming months.

Picking my favorites for the year seems somewhat silly, since such choices are increasingly personal in the way picking one’s favorite movie or TV show is not. With so many niche markets and new points of distribution and production, it is increasingly hard to find a group of people sharing your own musical taste. So I offer mine here in the spirit of celebrating the diversity and possibilities of pop music.

Looking over my own playlists for the last year, I see a tendency toward a more downbeat and experimental pop than was to be found in my choice of last year’s favorite album. In 2008, I celebrated Girl Talk’s Feed the Animals for its creation of new musical life from the genetic stuff of other people’s music. But Feed the Animals was a product of a kind of excess and exuberance (and even optimism) that doesn’t quite jibe with 2009’s more minimalist moroseness. This year, my virtual turntable was spinning The Dirty Projector’s brilliant but hard Bitte Orca, Atlas Sound’s awkward soundscapes (somehow simultaneously chirpy and bleak) on Logos, and St. Vincent’s schizophrenic Actor. What all of these have in common is a strange brew of pop hooks and willful difficulty, of cuteness and scars. But in the end the album I listened to the most, the one that seemed to be the most powerful medicine during a year when medicine was much needed was the debut self-titled album from XX. I do not believe it is the best album of the year (all the other albums I mentioned are, by whatever objective standard is possible in such calculations, “better”). But in its wan, melancholy minimalism, and for all the reasons that it is in every way the opposite of Girl Talk’s Feed the Animals, it will

remain forever my soundtrack of 2009.Video Games

Video games present a whole set of different challenges for a casual gamer like myself. I don’t own a PS3, so Uncharted is merely the platonic ideal of Game of the Year for me. Nonetheless, even if I owned every console and had the time to play every game (which, I hesitate to add, I am grateful I do not), I am confident that I would settle on my current choice for best game of 2009: Scribblenauts for the Nintendo DS. Yes, I know that there were some tremendous games this year, including the monumental Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 and Assassins Creed II. And Batman: Arkham Asylum proved, at last, that comics and video games could be combined to produce true magic. But Scribblenauts got back to the basics of making video games creative and surprising.

For those who haven’t played it, the premise is both simple and somewhat unbelievable. You are given a series of challenges through which you have to negotiate our hero, Maxwell. To solve them you … write words. And the words you write come to life on the screen as objects which Maxwell can use to defeat enemies, overcome obstacles, or beat a hasty retreat. It is far and away the most inventive game I have played in some time, but also the most immersive, despite being animated in a pared-down 8-bit style that runs contrary to everything we’ve been told by the industry about how to create more interactive, immersive gaming experiences. Now I just want a console version for my Wii so the whole family can more easily play it together.The Year in Pop

As different as they are, I realize now that what all my picks have in common is a restrained, back-to-basics aesthetic – a return to some of the fundamental pleasures and building blocks of the media in which they are working after a decade of working the digital toolset in the other direction. It seems a fitting end to the first decade of the 21st century, and not only because of the obvious reality of the Great Recession which has defined so much of this year. No, it is an appropriate capstone to the decade because it is a signal that after a decade of relishing in the seemingly inevitable tendencies of the digital revolution to push towards more layers, bigger sounds, and vaster budgets ($500 million for Avatar?), it might be time for the next stage in this pop renaissance – where restraint and economy are increasingly valued for the ways in which they remind us why we love this stuff so much in the first place.Jared Gardner teaches American literature, film and popular culture at the Ohio State University. He can be reached at editor@guttergeek.com

Writer's Web site www.jaredgardner.org© 2010-12 Short North Gazette, Columbus, Ohio. All rights reserved.

Return to Homepage www.shortnorth.com